Credit: Nub Cake (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons.

Turkey concluded its constitutional referendum on April 16, with the proposed constitutional amendment passing by a narrow margin amid fraud allegations by the opposition. The ruling party-led camp for constitutional change won 51.4 percent of the votes, while the secularist-Kurdish alliance received 48.5 percent of the votes. From the perspective of the current government's critics, Turkey’s democracy has come to a sharp end. In the wake of a referendum barely won, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will assume control over the state's judiciary, legislative, and executive branches. In contrast, the government and President Erdoğan himself maintain that the new system will not only empower the parliament, but will also ensure the country's stability as it faces external and internal threats to its national security and territorial integrity.[1]

The fate of modern Turkey’s democracy is still dependent on post-referendum policies of both the government and the opposition, as both camps have been strengthened and unified by the referendum process. Given that the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi - AKP) could not secure a significant majority for its referendum victory – with the opposition bloc receiving only 2.9 percent less votes than the AKP-MHP alliance – the referendum results have weakened AKP's conservative nationalist partner, the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi - MHP). In the months ahead, Turkey's post-referendum politics may prove more important for the country’s 94 year-old democracy than the results of the recent referendum.

The AKP-MHP Alliance

The constitutional referendum process commenced in late January, with the Turkish parliament's passage of an 18-article bill on amendments to the constitution, proposed by the AKP-MHP bloc.[2] However, the rapprochement between the two parties, once locked in a fierce dispute, traces back to 2016. Responding to the failed coup of July 15-16, 2016, the ultranationalist MHP pledged unconditional support to AKP. According to pro-AKP media outlets, the aggressively energetic MHP-linked Grey Wolves, also called Idealist Hearths (Ülkü Ocakları), stood shoulder to shoulder with AKP supporters as street clashes with perpetrators of the failed coup erupted across the country.[3] MHP explained that the party was taking a stand against the disruption of the democratic process by a military coup, rather than supporting AKP. However, critics of the party saw this rapprochement with AKP as a mechanism of MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli’s strategy, using the ruling party's support to suppress opposition within his party.

In mid-2016, the ideological shift in AKP’s discourse towards an ultra-nationalist rhetoric constituted the backbone of an enhanced rapprochement with MHP. The two parties began using the same rhetoric as they responded to challenges posed to national security by Kurdish territorial gains in Syria, and post-coup authoritarian measures implemented to suppress the secularist opposition. More precisely, rhetorical changes occurred only in AKP’s discourse, while MHP maintained its well-known nationalist position, with a slight shift to accommodate AKP’s seemingly authoritarian ambitions.

It remains unclear whether AKP’s rapprochement with MHP was ultimately motivated by securing Devlet Bahçeli’s support for the proposed constitutional bill –particularly because Bahçeli was the first leader to reject the possibility of forming a coalition government with AKP after the June 2015 elections.[4] However, shortly after the failed coup attempt in 2016, AKP was able to transform its close relationship with MHP into a majority parliamentary bloc, supporting the passage of the proposed 18-article bill. Calculations for the prospective referendum started after this point, with a simple mathematical approach: MHP and AKP votes combined against the possibly united bloc of opposition parties.

AKP’s mathematical rationale for the constitutional referendum was quite simple. In the November 2015 elections, the ruling party had received 49.49 percent of the votes and MHP had received 11.90 percent.[5] Based on the assumption that the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi - HDP) and the secularist-Kemalist Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi - CHP) would vote against the pro-Erdoğan constitutional amendment, AKP could achieve a substantial majority of over 55 percent “Yes” votes through an alliance with MHP. Meanwhile, unlike previous years, the Turkish government was no longer in peace talks with the separatist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan - PKK), nor was it entrenched in any political situation requiring pluralist rhetoric that would make an alliance with MHP impossible.

As apparent from the referendum results, the parliamentary alliance that granted success to the AKP-MHP bloc failed to garner over 55 percent of the referendum votes. “Yes” votes hovered slightly below the 51.6 percent that President Erdoğan had received in the 2014 Presidential Elections, exhibiting no MHP support.[6] The results implied two possibilities: either MHP or AKP supporters had betrayed their party and voted against the constitutional amendment. The second possibility was immediately dismissed by AKP-linked media, leading to cynical quips on social media that Devlet Bahçeli might have been the only MHP supporter to have voted “Yes” in the referendum.

The Kurdish Factor

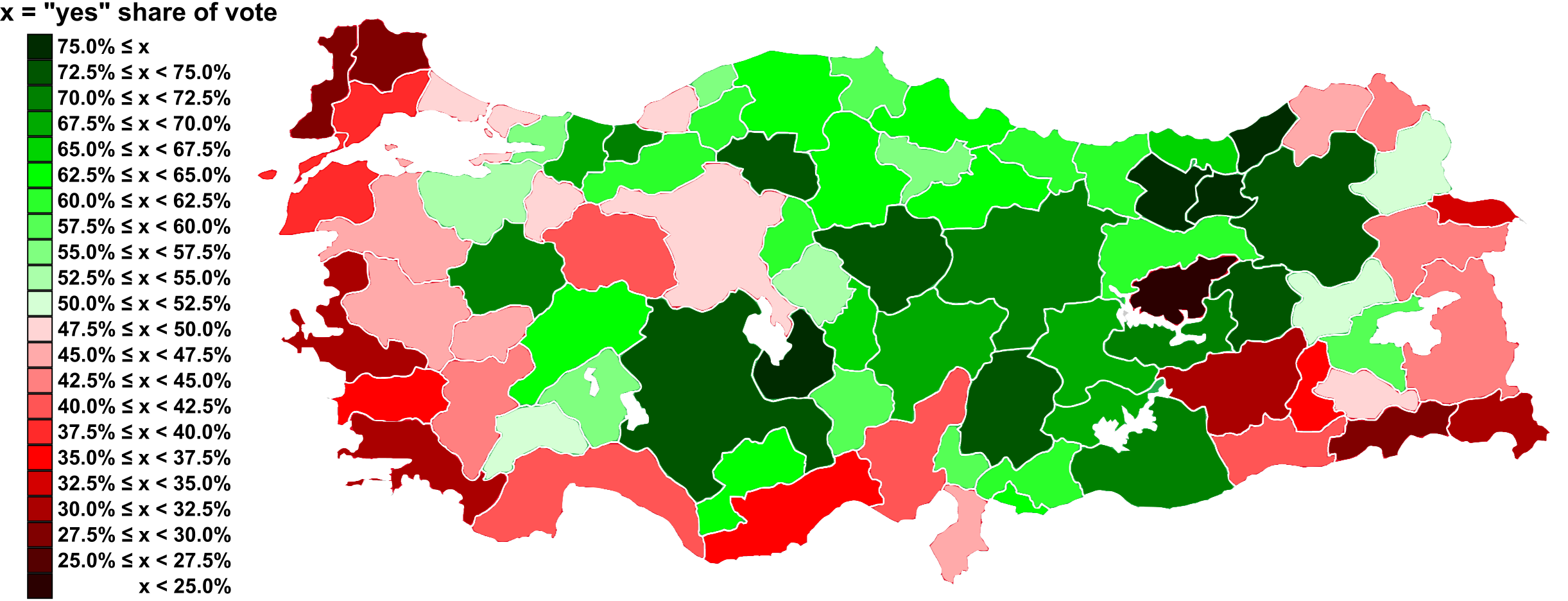

Ironically, the AKP-MHP bloc’s narrow success in the April 16 constitutional referendum was facilitated by Kurdish voters, from the predominantly Kurdish-populated southeast. Although there are no numerical records of the amount of votes from each party, results in the southeast indicated that a substantial portion of the HDP’s base voted “Yes.” Referendum results from the Kurdish cities of Ağrı, Bitlis, Van, Muş, Hakkari, Tunceli, Şırnak, Bingöl, Siirt, Diyarbakır, Şanlıurfa, Batman, and Mardin were 10 to 20 points lower than the percentage of votes for the pro-Kurdish HDP in the last elections. To be more precise, the AKP-MHP bloc received 450 thousand more "Yes" votes from Kurdish cities than the parties received in the last elections in this region. Nonetheless, regardless of increased votes for the AKP-MHP-led “Yes” bloc, the “No” camp had an absolute victory in the Kurdish region.[7]

Considering that the AKP-MHP bloc won the referendum with a very narrow margin of 2.8 percent, the roughly one percent extra contribution from the Kurdish region may have played a decisive role. Additionally, although it is almost impossible to assess the distribution of “Yes” or “No” votes in western Turkey, where the results are not determined by ethnic votes, the “Yes” camp also won in predominantly Kurdish-inhabited districts of Istanbul, such as Bağcılar.[8]

The HDP had two consecutive and considerable elections victories in the Kurdish region of the southeast in 2015. In the June 2015 elections, the party got 13.1 percent of the overall votes, allowing the party to overcome the electoral threshold for parliament of 10 percent for the first time, with the highest number of votes the Kurdish movement had ever gained in Turkey.[9] In the snap elections of November 2015, HDP votes were reduced to 10.7 percent, but this was still enough to get over the threshold that had prevented Kurdish parties from entering parliament since the early 1990s.[10]

During the period preceding the constitutional referendum, HDP adopted a strictly anti-presidential system approach, campaigning for the “No” camp in the Kurdish region and throughout the country. Parallel to the AKP-MHP bloc’s strategic reliance on previous election results, the HDP sought to assume a key role in blocking the proposed constitutional amendment by maintaining its 2015 margins, especially in the Kurdish southeast. However, the pro-Kurdish party appears to have overlooked the thematic differences between its campaigns for the elections in 2015 and the referendum in 2017 – an oversight which might have resulted in the dip in HDP votes among the Kurdish minority. In contrast to the election campaigns of 2015, HDP’s "No" campaign failed to appeal to the Kurdish nationalist pragmatism indigenous to the Kurdish southeast. It fell short of promising stabilized relations with the central government in the event of a ballot box victory, a promise which had gained the party the Kurdish middle-class vote in the 2015 elections. In other words, in 2015, the Kurdish middle-class of the southeast was convinced that a strengthened HDP position in the parliament would bolster peace talks with the government, as AKP would have retained its authoritarian monopoly after the elections. In 2017, the assumption that AKP and Erdoğan would continue to rule the country after the referendum remained unchanged, but a victory for the “No” camp did not promise the stabilization of state-Kurd relations.

Turkish Democracy at Crossroads: Post-referendum Era

The narrow margin win for the AKP-led “Yes” bloc in the referendum could still contribute to Turkish democracy, despite concerns that President Erdoğan will choose a more autocratic path in the post-referendum era, disregarding the 48.5 percent of “No” votes. The "No" bloc's significant success in attracting almost half of the voters is likely to strengthen the opposition - if not unite it - while AKP and Erdoğan consolidate their control over state institutions. As AKP’s image of invincibility has been significantly damaged by the referendum results, in the upcoming elections of 2019, the opposition may have better chances of forming a consolidated front challenging Erdoğan’s AKP. Although AKP may still require MHP’s parliamentary support to pass a large number of transition laws in the next two years, the ruling party may be loath to rely on ultranationalists, considering the AKP's vested interest in maintaining votes from the non-HDP-aligned Kurdish middle class.

The AKP-MHP failure to achieve significant success in the referendum will not necessarily produce a rapprochement between the AKP and the pro-Kurdish HDP, but it will definitely diminish the nationalist tone the government directs at the Kurdish minority. Referendum results and ongoing internal disputes have a strong potential to further weaken the MHP, if not disintegrate it. Non-HDP Kurds could gain a stronger position in the current political equilibrium by simply replacing the MHP as an effective ally for the AKP in the next elections. Such a pragmatic relationship between middle class Kurds and the AKP may fall short of renewing the peace talks with PKK, but would limit the pressure imposed by the AKP on the HDP since 2015.

None of the aforementioned prospects for the post-referendum era in Turkey can protect modern Turkey’s democracy if, while consolidating control over the state, AKP and Erdoğan incline towards a more authoritarian rule.

Ceng Sagnic is a junior researcher at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies (MDC) - Tel Aviv University. He serves as the coordinator of the Kurdish Studies Program and editor of Turkeyscope. cengsagnic[at]gmail.com