On 15 January 2022, Malik Faisal Akram, a British Muslim man who was not affiliated with any specific terrorist organization but was known as an extremist, stormed a synagogue in Texas and took four Jews hostage.[1] Akram, who eventually was killed by law enforcement agents, demanded to release Dr. Aafia Siddiqi, an American-Pakistani female who was accused of terrorism and consequently jailed. Since her imprisonment, many advocated for her release.

Campaigns for her release were echoed on the internet and social media. Jihadi organizations also tried to hasten her release by abducting Westerners in North Africa, the Middle East or Asia. However, the most prominent and consistent support for Siddiqi did not come from those jihadi organizations, but rather from the British Salafi-jihadi milieu. Of these British Salafi extremists, the most vocalist, provocative and influential is Anjem Choudary, who has orchestrated well-coordinated online campaigns in order to raise awareness of jailed Siddiqui.

Aafia Siddiqui is a Pakistani neuroscientist who lived in the United States with her husband and three children. The September 2001 attacks radicalized her. In 2003, she left her husband and the United States and travelled to Pakistan. A year later, she was considered as a threat by US federal authorities. She was last seen in July 2008 in Afghanistan, when she was arrested along with one of her children by Afghan officers.

During the trial, it emerged that she possessed “numerous documents describing the creation of explosives, chemical weapons, and other weapons involving biological material and radiological agents”. Some documents Siddiqui obtained “included descriptions of various landmarks in the United States, including in New York City”. The documents she held also contained details of US military targets, “excerpts from the Anarchist's Arsenal, and […] numerous chemical substances in gel and liquid form that were sealed in bottles and glass jars”.[2]

She also tried to shoot US personnel who came to question her while in detention. Transferred to the US in 2008, Siddiqui was convicted on terrorism charges in 2010. She was sentenced to 86 years in prison and is being held in Texas, not far away from the synagogue that was attacked.[3]

Siddiqui is believed to have direct ties to al-Qaeda, and the organization and its affiliates reflected it in actions. After she divorced from her first husband, she allegedly married a prominent al-Qaeda member, the nephew of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of the September 11 attacks. Days after her sentence, the Taliban kidnapped a British aid worker and three of his local colleagues and proposed to exchange them for Siddiqui.[4]

In December 2010, al-Qaeda urged Muslims to avenge Siddiqui. In 2011, a Swiss couple was kidnapped in Baluchistan by the Pakistani Taliban in order to release her. In 2012, the Afghan Taliban demanded the release of Siddiqui in exchange for the release of a captive US soldier who was eventually released in 2014 in exchange for five senior Taliban leaders. In 2014, following the death of an American captive at the hands of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) militants, the organization released a video in which the spokesperson demanded to know the fate of Siddiqui.[5]

On the internet, the campaign to free Aafia gained popularity, mainly in Pakistan, but also among Pakistani migrants in the West. The Pakistan-based Aafia Movement is just one example of the efforts to hasten her release. Aafia Movement’s website was created in 2010 and is hosted on the Arizona-based company Web Commerce Communications Limited dba WebNic.cc.[6]

The Aafia movement’s content is widely shared on social media. For example, a Facebook page called “Free Aafia Siddiqui Now”, which has more than 60,000 followers, states that its purpose is to “Calling on all people of conscience to unite and speak out about the injustice caused to Dr. Aafia Siddiqui”.[7] This page contains documentation of pro-Aafia demonstrations from around the world. On Twitter, the Aafia Movement account has more than 12,000 followers.[8]

Anjem Choudary is a British Salafi extremist preacher that has a long history of activism for jihad. He was the pupil of Sheikh Omar Bakri Muhammad, one of the founders of “Al-Muhajiroun”, an organization that advocated for jihad and praised al-Qaeda. After Al-Muhajiroun was banned and Bakri Muhammad left Britain to Lebanon, Choudary replaced him as the prominent figure of the British Salafi-Jihadi milieu. Among the groups that replaced Al-Muhajiroun were “Islam 4 UK”, “Muslim Against Crusaders”, “Al-Ghuraba”, and “Need 4 Khilafa”. The later emerged in parallel to the rise of the Islamic State (IS) terrorist organization, which was supported by Choudary and his friends.

Due to his support of IS, Choudary was jailed in 2016 but released in 2018.[9] He was banned from using social media until 2021, and soon after the ban was lifted, he returned to advocate for Muslim prisoners via new Twitter storms. According to MEMRI, “It is also likely that Choudary is affiliated with a new English-language magazine, Al-Aseer (The Prisoner), which campaigns to free Muslims imprisoned on terrorism charges and has been endorsed by pro-ISIS Telegram channels”.[10]

It is noteworthy that the campaign was supported by many Muslims worldwide, including in the US. For instance, Council on American–Islamic Relations (CAIR), the Muslim Brotherhood’s arm in the USA, organized demonstrations calling for her release. CAIR’s efforts were supported by the anti-Israel political activist Linda Sarsour, who also advocated for Siddiqui.[11]

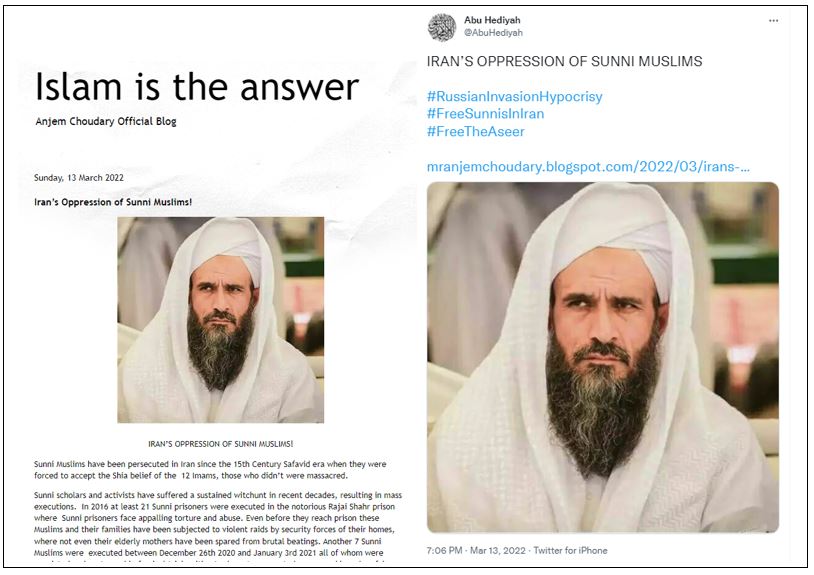

However, the online campaigns for Siddiqui link Muslims from around the world to Choudary’s campaigns, thus exposing them to Choudary’s and his friends’ extremist views and agenda, which they promote by using hashtags such as #freeaafiasiddiqui, #free_sister_aafia, and #FreeTheAseer. For example, on 13 March 2022, Choudary published a post on his personal blog, which was since deleted, in which he attacked Iran’s oppression of Sunni Muslims.[12] On the same day, the Twitter account of “Abu Hediyah” (@AbuHediyah), which was created in March 2022 and has 21 followers, echoed Choudary’s message by using the same headlines and the same picture used by Choudary. They also added the hashtags #RussianInvasionHypocrisy, #FreeSunnisInIran, and #FreeTheAseer, and a link to Choudary’s blog.[13]

On 18 March 2022, a Twitter account named “Team Aafia Offical” (@Teamaafia1), which was created in March 2020 and has more than 1500 followers, advocated for Muslim prisoners, writing “We pray that every innocent is released from behind the bars, and reunited with their families”. The account’s owner added the hashtags #FreeTheAseer, #AafiaSiddiqui, #TeamAafia, and #FreeAafia. A day after, a Twitter account called “Ghost pepper” (@AintRice) which was created in January 2020 and has more than 120 followers, also advocated for Siddiqui by using the hashtags #freeaafiasiddiqui, #free_sister_aafia, #RussianInvasionHypocrisy, #FreeTheAseer, and #FreeSunnisInIran.[14]

Such online activism illustrates how Choudary and other Western Salafi extremists not only continue to spread their messages, but also how they expose many others to an extremist worldview that supports terrorism, and which is linked to Choudary, a convicted jihadi propagandist who is known for grooming and radicalizing Muslims.

Considering the above, it is clear that the threat from Choudary and his associates, who continue to incite against democracy and the “enemies of Islam”, remains unchanged. Accordingly, it is not inconceivable that others will also attempt to carry out attacks in order to promote the release of the righteous and other Muslim prisoners jailed in Western prisons for terrorist activity. Dealing with the potential threat requires familiarity with the Salafi-extremist discourse and exposing the actions of these extremists on behalf of Muslim prisoners accused of terrorist activity, both in the virtual world and on the streets.

Dr. Ariel Koch is a postdoctoral researcher at the Lauder School of Government Diplomacy and Strategy, The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) in Herzliya; and Senior Fellow at the Centre for the Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR), London.

[1] Annabelle Timsit, Souad Mekhennet and Terrence McCoy, “Who is Aafia Siddiqui? Texas synagogue hostage-taker allegedly sought release of ‘Lady al-Qaeda’” The Washington Post, 16 January 2022; Michael Kugelman, “How Aafia Siddiqui Became a Radical Cause Célèbre” Foreign Policy, 18 January 2022.

[2] United States of America v. Aafia Siddiqui, Complaint, Southern District of New York, Justice.org, 31 July 2008.

[3] Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui” The Guardian, 24 November 2009; Michael Kugelman, “How Aafia Siddiqui Became a Radical Cause Célèbre” op. cit.

[4] “Taliban kidnap British aid worker, demand prisoner swap for Aafia Siddiqui” Christian Science Monitor, 27 September 2010.

[5] Khaled Ahmed, “Swapping of Aafia Siddiqui for Shakeel Afridi has been in the works for a while” Indian Express, 21 September 2019; “Bimonthly Report – Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites The First Half of December 2014” International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, December 2014, p. 11.

[6] Aafia Movement, Domaintools; accessed 23 March 2022.

[7] FreeAafiaSiddiquieNow, Facebook; accessed 23 March 2022.

[8] @FowizaSiddiqui, Twitter; accessed 23 March 2022.

[9] “Anjem Choudary: Radical preacher released from prison” BBC, 19 October 2018.

[10] “British Pro-ISIS Preacher Anjem Choudary Uses Texas Synagogue Hostage Incident As Opportunity To Launch New Twitter Storm Demanding Release Of Aafia Siddiqui” MEMRI, 17 January 2022.

[11] CAIR Texas, “Free Dr. Aafia! - Discussion with Linda Sarsour on the Renewed Campaign to #FreeAafia” YouTube, 11 November 2021.

[12] “Iran’s oppression of Sunni Muslims” Mr Anjem Choudary Blog, 13 March 2022. The blog has been removed; last accessed 13 March 2022.

[13] @AbuHediya (Abu Hediyah), Twitter, 13 March 2022; accessed 23 March 2022.