On March 31, sixteen recently elected Arab and Druze Knesset members were sworn in and took their seats in the 20th Knesset. Of this group, 12 belong to "the Joint List" while each of the remaining four represent different Jewish-Zionist parties, including the center-left Zionist Camp, the left-wing opposition Meretz, the victorious Likud (led by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu), and Yisrael Beitenu, a member of the previous governing coalition. This is the largest number of Arab and Druze MKs elected to the Knesset since its establishment in 1949. Perhaps even more noteworthy, the Joint List, which is now the Arab public's major political representative body in the Knesset, is the third largest faction in parliament, with a total of 13 seats (including 1 Jewish MK), trailing only Likud (with 30 seats) and the Zionist Camp (with 24).

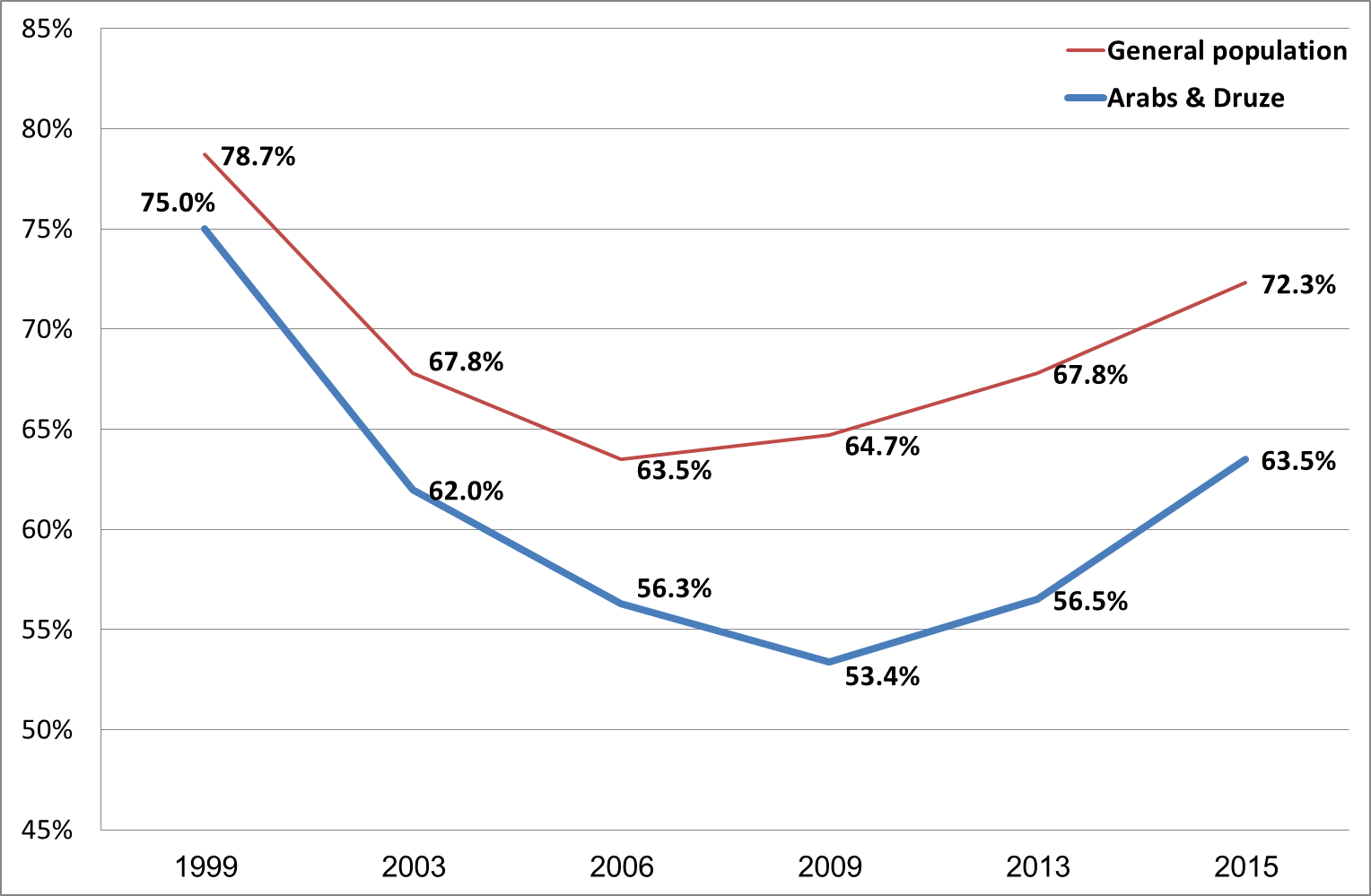

It is doubtful whether anyone among either the Arab or Jewish publics was surprised by these results. The Joint List is a collaboration of four parties – Hadash (Democratic Front for Peace and Equality), a party that represents the communist stream in Arab politics and advocates Jewish-Arab cooperation; and three parties that represent the national and Islamist streams: Balad (National Democratic Assembly), Taʾal (Arab Movement for Change), and Raʾam (The United Arab List, which represents the southern wing of the Islamic Movement). Since the Joint List was initially established on January 23, 2015, talk on the Arab street focused on the anticipated boost to the Arab sector's voter turnout in the elections, which would increase Arab representation in the Knesset. As it turned out, voting rates in the Arab public in 2015 (63.5%) were significantly higher than in 2013 (56.5%). The Joint List’s historic achievement brings to the fore several important questions concerning the future of Arab politics in Israel. The first and perhaps the most interesting question is whether the dramatic rise in voting in the recent elections constitutes a turning point in the political participation of the Arab public.

Prior to the latest election, voting rates in Knesset elections among the Arab public over the last decade were significantly lower than in the past, hovering around 55 percent in the last three elections (2006, 2009 and 2013). These figures were undoubtedly affected by the violent confrontations in the north and center of Israel in October 2000, in which 13 young Arabs were killed by police gunfire. These events led to a sharp decline in voter turnout in the Arab and Druze sectors during the 2003 election. Voting rates declined further in 2006, owing to a combination of political indifference that gradually permeated throughout the Arab public and an explicit call by nationalist and Islamist organizations to boycott Knesset elections. One of the explanations for this sector's continually declining confidence in the Knesset was the dominance of the right-wing Jewish parties, and the increasing number of legislative initiatives that these parties put forth, which are viewed as discriminatory by the Arab public.[1] One such initiative that triggered criticism in the Arab public was the “pledge of allegiance” bill, endorsed by the Likud-led government in October 2010. According to the bill, all non-Jewish – mainly Arab – applicants for Israeli citizenship would be obligated to pledge allegiance to the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state.[2]

The establishment of the Joint List played a critical role in reversing this decade of political apathy. According to an Arab public survey conducted one month before the elections by the Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation, almost one half of the Arab respondents (44.8%) confirmed that the establishment of the Joint List had a positive impact on their voting intentions in the upcoming elections. The survey also predicted the rise in voting turnout, as a full three-quarters of the respondents stated that they intended to vote on Election Day.[3] Moreover, according to the survey, the majority of respondents (68.3%) believed that the Knesset would, from now on, be an effective arena for political action for the Arab public in Israel.

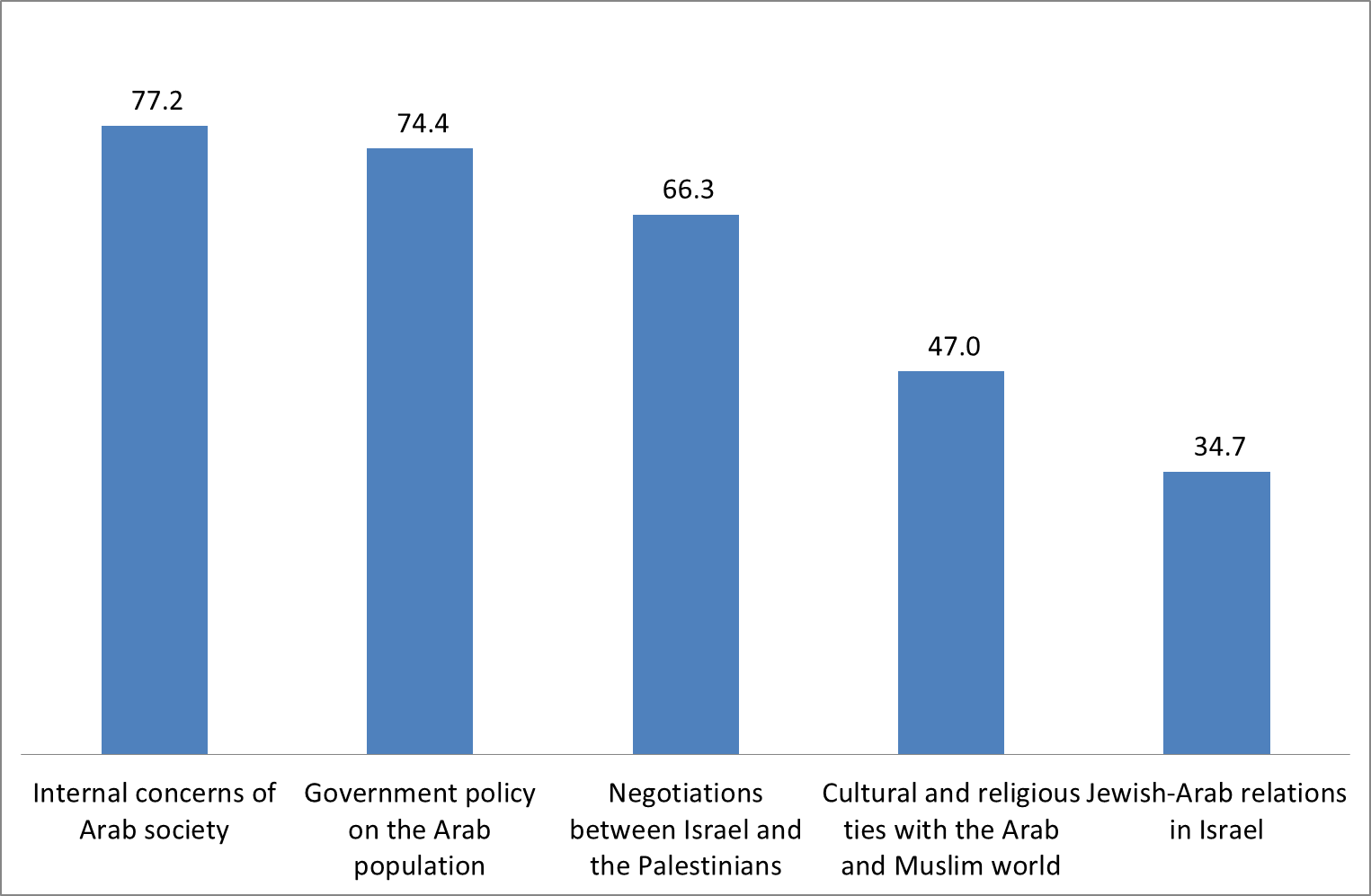

Although the record high voting rates in Arab localities (the highest since 1999) may indicate that political participation in the Knesset has once again become important to the Arab public in Israel, this does not mean that the Arab sector's political agenda will resemble that of the past. In the 1990s, Arab political discourse mainly stressed efforts to achieve peace between Israel and the Palestinians and equality between Jews and Arabs in Israel, but in more recent years, the Arab public has adopted a more inward-looking perspective, focusing on its status as a national and civic minority in Israeli society, and the need for solutions to the concerns and problems plaguing Arab society in Israel (healthcare, education, violence, women’s status, etc.). These changes were confirmed in the Konrad Adenauer Program survey, where respondents ranked the internal problems of Arab society and the government’s policy toward the Arab population as the two most urgent problems that should be tackled by the Arab MKs after the election. The negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians ranked only third in order of importance. (See Figure 2; respondents rated their responses on a weighted scale from 1 to 100.).

An important question raised by this year's election is whether the momentum towards increased cooperation within the Arab political class triggered by the Joint List’s establishment can be sustained, and if so, what it will be used to achieve. Since the Joint List was established, there has been an extraordinary sense of unity on the Arab street.[4] These sentiments are fueled by the broad Arab pre-election support for the Joint List, which was considered a means of guaranteeing Arab representation in the Knesset despite the elevated parliamentary threshold.[5] The Joint List’s leading campaign slogan was Eradat Shaʿb (A Nation’s Will), undeniably similar to the term Eradat al-Shuʿub (The Will of Nations), attributed to the series of Arab Spring uprisings in neighboring Arab countries. At the mid-February convention in Nazareth that officially jump-started the Joint List’s campaign, List leaders emphasized that the formation of the Joint List should be a constructive lesson not only for the Arab public in Israel, but also for the Arab nations in neighboring countries, that the common national denominator is stronger than any other separating lines based on religious or political affiliations.[6]

The Joint List thus became a tangible expression of the Arab minority’s self-definition as a consolidated national collective, but it is not clear whether it has reached a consensus on a national agenda. After all, the parties that comprise the Joint List hold political and ideological positions that may be difficult to reconcile with one another. Members of the Joint List include, at one end, religious and conservative individuals identified with the Islamic Movement, and at the other end —secular individuals with more progressive views regarding individual rights, who mainly identify with the communist party.

Moreover, the word “Arab” is conspicuously missing from the Joint List’s name, even though the vast majority of its members and voters are Arabs. This is not unintentional, since Hadash advocates joint Arab and Jewish civic action. The omission seems to have worked: support for the Joint List's constituent parties in Jewish communities remained the same as it had been in the 2013 election.[7] It is doubtful, however, that Jewish voters who remained faithful to Hadash by voting for the Joint List will be able to identify with the Joint List's slogan, A Nation’s Will.

Where, then, will the newfound sense of unity and optimism regarding parliamentary politics be directed? Will efforts focus on parliamentary politics, for example, by campaigning for an increased number of Arab MKs in Knesset committees and transforming the Knesset into a more effective arena for public action on behalf of the Arab public? Or, having achieved the sought-after unity in the Knesset, will the positive momentum be diverted to issues outside the Knesset, for example toward a reform of the Supreme Follow-Up Committee[8] and its transformation into an external, non-parliamentary leadership body of the Arab public? This choice reflects the ongoing competition between two rival approaches: that of Hadash, which advocates joint parliamentary action involving all citizens, both Arab and Jewish, and that of the Islamic Movement and Balad, for whom parliamentary politics is merely a political means for serving the Arab minority and not its ultimate goal.[9] For the Islamists, the ultimate goal is to preserve a religious Islamic way of life and Islamize Arab society, while the goal of the nationalists (represented by Balad) is to preserve the Palestinian national consciousness of the Arab minority and ultimately de-Zionize the State of Israel.

The results of the recent elections have proven that Arab representation in the Knesset has reached a historic peak. However, the effects of this achievement depend on the conduct of the Joint List’s members. The Arab public has high expectations for its newly elected representatives in the Knesset. Will these elections mark a turning point not only in the political behavior of Arab voters but also of the Arab Knesset members? Will the Joint List’s components forgo tiring ideological bickering in order to work together to maximize the benefits for their voters? We can only wait to learn the answers to these important questions.

Arik Rudnitzky is the Project Manager of the Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies (MDC), Tel Aviv University. His fields of research include political, national, and social developments in Arab society in Israel.

Notes

[1] According to the “Index of Arab-Jewish Relations” survey, the proportion of Arab respondents who stated that they had no confidence in the Knesset rose from 58.3% in 2003 to 66.3% in 2013. See: Sammy Smooha, Still Playing by the Rules: Index of Arab-Jewish Relations in Israel, 2013 (Jerusalem and Haifa: Israel Democracy Institute and the University of Haifa, 2015).

[2] See: Uzi Rabi and Arik Rudnitzky (editors), The Proposed Pledge of Allegiance and the Arab Citizens of Israel (Tel Aviv University: The Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation, October 28, 2010).

[3] Itamar Radai and Arik Rudnitzky (editors), Survey of Political Attitudes in the Arab Population in Israel in Anticipation of the 20th Knesset Elections (Tel Aviv University: Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation, 15 March 2015) [Hebrew].

[4] Noteworthy in this context is the fact that contrary to previous election campaigns, where each party ran separately, this time the ideological spokesmen of each party comprising the Joint List downplayed the ideological differences between their parties, thus demonstrating their commitment to the newly established joint framework.

[5] In March 2014, the Israeli Knesset passed the “Governance Law” according to which the electoral threshold was raised from 2 percent to 3.25 percent. This legislation was fiercely criticized by Arab MKs who perceived it as yet another measure targeting Arab representation in the Knesset. Haaretz, March 12, 2014.

[6] See: “The Joint List launched its election campaign in a well-attended conference,” www.bokra.net, February 14, 2015 [Arabic].

[7] According to statistics of the Central Elections Committee, the Joint List received 3.8% of the votes outside Arab localities and mixed Arab-Jewish cities. In 2013, the parties that currently constitute the Joint List together received 3.6% of the votes outside Arab localities and mixed cities.

[8] The Supreme Follow-Up Committee was established in 1982 as an extra-parliamentary body that aims to change state authorities’ policy regarding the Arab minority. The Committee serves as an umbrella organization both for parliamentary Arab parties and other popular ex-parliamentary movements in the Arab street. A strong internal debate in recent years in the Arab sector has centered on whether the Committee’s members should be elected directly to their office by the Arab public, thus becoming a de facto “Arab parliament”, or whether the Follow-Up Committee should continue in its current structure as a leadership organization whose decisions are not necessarily binding.

[9] It is not surprising that the nationalist and Islamic Movement leaders in Arab society contended, after the elections, that the Joint List should not be considered a unifying framework for the entire Arab public since certain groups do not participate in Israeli parliamentary elections, and therefore practical action should be taken to reinforce the status of the Supreme Follow-Up Committee with the aim of transforming it into such a unifying framework. See Panorama, March 27, 2015 [Arabic].