AMISOM Public Information, from Flickr [Public Domain]

Introduction

Salafi-jihadi groups (SJGs) have become a significant challenge and threat to global security and to the political stability of many countries during the past few decades.[1] The emergence of al-Qaʿeda and the Islamic State, and the catastrophic consequences of their activity remain vivid in the memory of many. In recent years, as the resonance of al-Qaʿeda and the Islamic State's operations seems to be receding in the Middle East and Asia, Africa has become a rising sphere for the activity of SJGs. This article will elaborate on the issue of Salafi-jihadi activity in Africa, its transnational classification, and on two of the groups that represent it today, al-Shabaab and Boko Haram.

Transnational SJGs in Africa

Transnational terrorism is a unique subset of terrorism with a distinct profile. Overall, it seems that the members of such an organization have several unique characteristics, as Patrick Stewart delineates:

First, they plan and carry out attacks across international borders, and their logistical arrangements typically span national frontiers. Second, although they may exploit local insurgencies, their motivations and objectives are global (or at least regional) in scope. Third, their ideology focuses on the transformation of international power and political relationships. Fourth, their membership crosses national, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds, often including veterans of nationality-based conflicts. Finally, they are typically organized as decentralized networks of affinity groups, with cells in multiple countries and flexible alliances with local extremists.[2]

By examining the characteristics of a transnational terrorist organization, one can deduce the potentially greater threat an organization of this kind may represent to a given country in comparison to an organization that is confined to clear national borders. Transnational terrorist organizations usually benefit from complex operational and recruitment abilities such as decentralized operational networks. These networks often operate in multiple countries and by members from a variety of cultural and national backgrounds. As this characteristic may prevent focusing resources on a specific area or community, countries may find it especially difficult to tackle this kind of organizations.

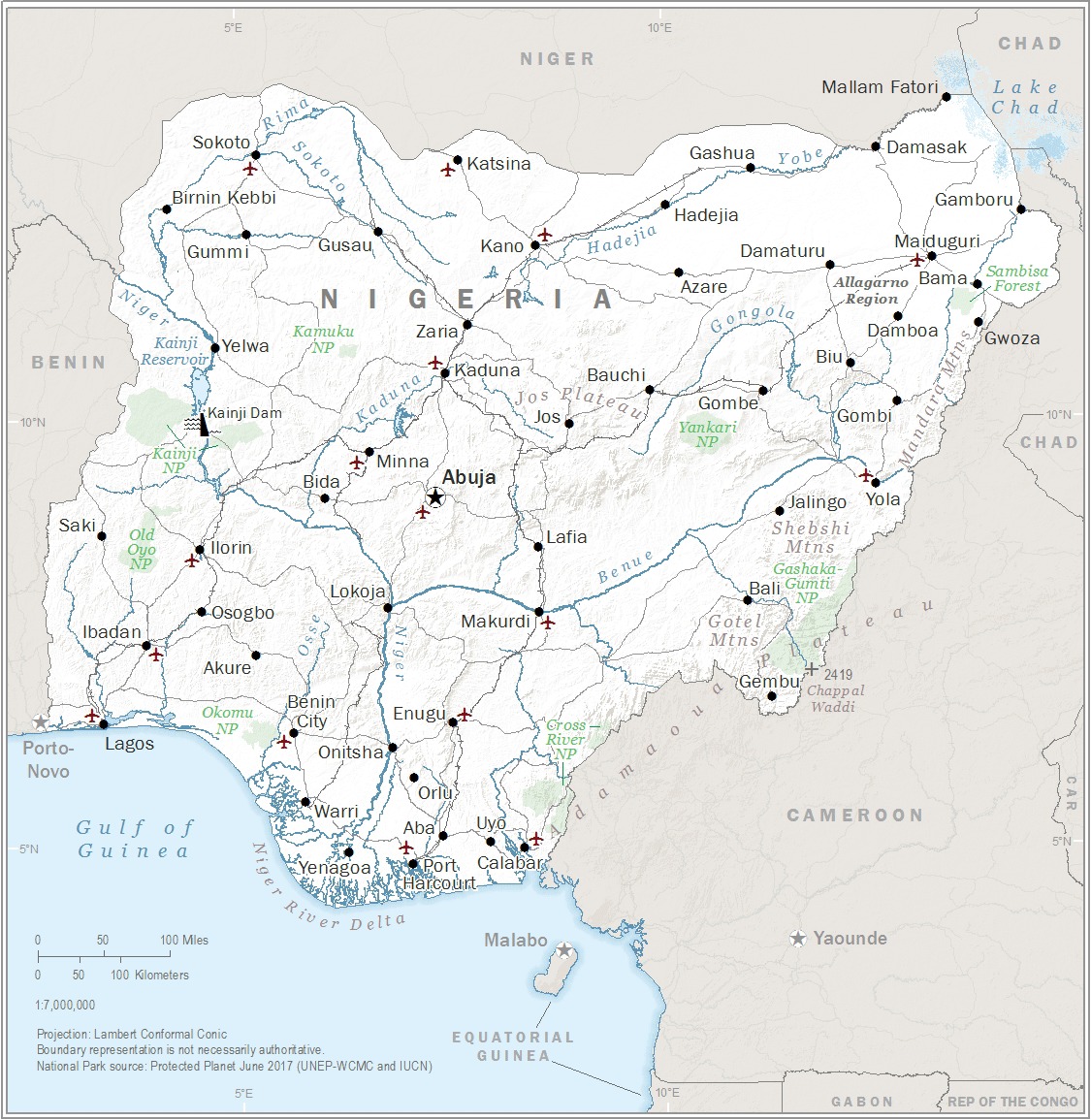

When examining Africa, the characteristics and operational abilities of transnational terrorism organizations mentioned above can describe two significant SJGs (among others) that operate in the continent today: al-Shabaab (AS), which operates in eastern Africa and especially in Somalia and Kenya; and Boko Haram (BH), which operates in the Lake Chad region and especially in Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and Niger. These two organizations are not only considered transnational in their modus operandi (e.g. cross-border operations, illegal trade, and multi-national recruitment) and areas of operations, but they also play an important role in the global Salafi-jihadi activity. AS is considered to be an ally, or affiliate, of al-Qaʿeda, while BH pledged its allegiance to the Islamic State.[3][4]

Al- Shabaab (AS)

AS was established during the Somali civil war that started in 1991 with the overthrowing of the regime of Siad Barre (1969-1991) and that is still going on today. The civil war was a confrontation between many different parties in Somalia, however, foreign interventions were a significant catalyst in the intensification of the conflict. One such intervention in 2006 was a major cause for the formation of AS – following a powerful offensive by a militant-group called the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) that took control of large parts of southern Somalia, the Western-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) requested aid from neighboring countries. In July 2006, Ethiopian forces invaded Somalia (one of many Ethiopian interventions in Somalia during that period) and began taking control of ICU territories. After months of fighting, the Ethiopian forces made significant gains and the ICU began splintering. A sub-group emerged containing more radical figures who started to gather around themselves young volunteers (hence the name al-Shabaab [The Youth]), who were deeply ideological and well-trained in combat, and they began engaging the Ethiopian forces. During the following months, AS became the main armed Islamist organization operating in Somalia, carrying out increasing attacks against foreign and domestic rivals, conquering territories, and exercising partial control over large swaths of the country.[5]

During the years following its emergence, AS managed to take root in many parts of Somalia and increase its transnational standing despite facing significant pressure from the Somali government and its allies (mainly Ethiopia, Kenya, and United States), and a multi-national force that was created to tackle AS (AMISOM).[6] In July 2010, AS carried out its first attack outside Somalia, when the group's suicide bombers attacked two pubs in Uganda, one of the countries comprising the AMISOM force. The post-attack investigation discovered that many of the terrorists involved were Kenyans and Ugandans and not of Somali descent, a fact that proved that AS was recruiting members from other countries. In September 2013, AS carried out another major attack outside Somalia, when four gunmen stormed the Westgate Mall in Nairobi and killed 67 people. The organization continued to operate in eastern Africa, and in April 2015 its militants stormed the University of Garissa in Kenya, this time taking a toll of 148 dead. Kenyan security forces struggled to cope with AS operatives who were born in the Muslim Kenyan community and amongst the Somali refugees living in Kenya who were familiar with the country and its characteristics. In January 2019, AS carried out its most recent major attack in Kenya when five militants (one of them a suicide bomber) attacked a hotel compound in Nairobi which concluded 15 hours later, with 21 dead and 28 injured individuals counted.[7]

The Nairobi attack in January 2019 was carried out by mostly Kenyan-born AS militants; this was also the case in the attack on Garissa University in 2015. By contrast, the militants who attacked the Westgate Mall in 2013 were largely foreigners. These three attacks suggest a trend of ongoing effort by AS to recruit home-grown militants for its attacks in Kenya.[8] During the year 2020 AS's operations in Kenya increased significantly - AS attacked Kenya about 30 times in the past decade, in just the first two weeks of 2020, the group recorded as many as five attacks, and at the end of March at least 15 attacks were reported to be linked to the group.[9] While the vast majority of AS's attacks are carried out in Somalia, most of its ‘foreign’ operations are located in the border area between Somalia and Kenya.[10] AS also maintains recruitment efforts in other regions in central Kenya that are distant from its ‘home base’ in Somalia.[11]

Boko Haram (BH)

BH was founded in 2002 in the city of Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state in northern Nigeria by Mohammed Yusuf, a local Islamic leader. At first the organization appeared to be concentrating on education - Yusuf established a complex in the city which included a mosque and a school mainly for children from poor families. However, the center also secretly served as a recruiting ground for future BH members. These potential members numbered more than 280,000 at the peak of recruitment, and came mainly from northern Nigeria and neighboring Chad and Niger. BH's official name is Jama'atul Ahlul Sunnah Lidda'wati Wal Jihad (JAS), which can roughly be translated as, The People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad. However, the popular name Boko Haram points to the ethnic origins of the organization. It derives from the Hausa word boko ('book') and the Arabic word haram ('forbidden'). Put together, Boko Haram means: Western education is forbidden.[12]

During its first years, BH considered the Nigerian regime as an opponent but at the same time it officially opposed violence (despite its members being involved in some clashes with security forces at that time).[13] This changed in June 2009, when a dispute between Nigerian police officers and BH members eventually led to the storming of the BH complex in Maiduguri by Nigerian security forces. An estimated 800 people were killed, Mohammed Yusuf was executed, and BH suffered a devastating blow.[14] After these events BH became much more violent and radical. The following years brought a sharp increase in BH's attacks against civilian targets, including Muslims, which was a significant cause for a split inside BH in 2016 that led to the creation of two factions who both pledged their loyalty to the Islamic State: the original faction that was now named JAS (as the initials of BH's official name), and a new faction, endorsed by the Islamic State as its affiliate, called ISWAP (Islamic State, West Africa Province).[15]

During the last several years both factions managed to take control of vast lands in Nigeria, Cameroon, Niger, and Chad, however, they were not in cooperation with each other, and sometimes even clashed in violent incidents.. This was achieved mainly by exploiting the lack of efficient counter-terror operations and cooperation between the countries' security forces, utilizing support from local populations with grievances towards the governments, and executing effective attacks on weak points, such as isolated army bases and unguarded villages and towns.[16] Following these gains, an international force composed of troops from those countries called the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) initiated an operation aimed to expel BH's factions from their newly-conquered lands.[17] In spite of the efforts of MNJTF and the national security forces of the different countries, the ongoing conflict with BH's factions is far from over. The Lake Chad region (that encompass vast territories within the four countries) is still a target for almost daily attacks of elements from both factions.[18] In a recent development, beginning in 2019, the Islamic State started attributing its insurgent activities in Mali and Burkina Faso to ISWAP, although those countries are considered to be the operational territory for another IS affiliate, ISGS (Islamic State in Greater Sahara). It seems that IS's leadership is aiming to promote ISGS's activities under ISWAP's brand, thus, expanding the territory under ISWAP's control from Burkina Faso in the west to Cameroon in the east, a vast area that includes large swaths of land within seven countries.[19]

Conclusion

Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram (both of its factions) provide an excellent representation of the rising threat of transnational Salafi-jihadi activity in Africa. Both organizations possess characteristics that present them as a significant challenge for the security and stability of the continent. The organizations' Salafi-jihadi orientation (and their alliances with al-Qaʿeda and the Islamic State), their cross-border operations and presence, and their ability to recruit members from different nationalities will require African countries and other international efforts to pay special attention to the potential danger that those organizations constitute.

As shown in this article, AS can no longer be considered solely a Somali problem, as its operations stretch to neighboring countries (especially Kenya). Similarly, BH is no longer only a Nigerian problem, but a regional one. This may have repercussions for the security and stability of many countries in Africa. In an even broader view, a dynamic of deteriorating security in eastern and western Africa may have broad political and economic implications for relations between countries, the activity of naval trading routes, and stability of the supply of oil, mainly in Nigeria.

Matan Daniel is a graduate student in the security studies program at Tel Aviv University. His primary research focus is Salafi-Jihadist activity in Africa and its interconnection with the global Salafi-Jihadist sphere.

[1] For more on the Salafi-jihadi movement and philosophy see Seth G. Jones, "A persistent threat: The evolution of Al Qa'ida and other Salafi jihadists," Rand Corporation, 2014.

[2] Patrick Stewart, Weak links: fragile states, global threats, and international security, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 63.

[3] "AL-SHABAAB," DNI, accessed: February 13, 2021.

[5] Lorenzo Vidino, Raffaello Pantucci, and Evan Kohlmann, "Bringing Global Jihad to the Horn of Africa: Al Shabaab, western fighters, and the sacralization of the Somali Conflict," African Security, Vol. 3, no. 4 (2010): 220-221.

[7] Matt Bryden and Premdeep Bahra, "East Africa’s terrorist triple helix: The Dusit Hotel attack and the historical evolution of the jihadi threat," CTC Sentinel, Vol. 12, no. 6 (2019): 5-8.

[8] Duncan E. Omondi Gumba and Mohamed Dagha, "Home-grown terror a worsening threat for Kenya", ISS Africa, January 29, 2019.

[9] Mohamed Daghar, Duncan E. Omondi Gumba and Akinola Olojo, "Somalia, terrorism and Kenya’s security dilemma," ISS Africa, January 22, 2020; Karen Allen, "Why is the US ramping up anti-terrorism efforts in Kenya?" ISS Africa, March 26, 2020.

[10] See for example: "Growing Desperation Over Al Shabaab Threat in Kenya’s North," Defense Post, February 10, 2021; Caleb Weiss, "Kenyan governor claims Shabaab controls over half of northeastern Kenya," FDD's Long War Journal, January 16, 2021.

[11] Guyo Chepe Turi, "Violent extremists find fertile ground in Kenya’s Isiolo County", ISS Africa, October 8, 2020.

[12] Daniel Egiegba Agbiboa, "Boko-Haram and the global jihad: 'Do not think jihad is over, Rather jihad has just begun'," Australian Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 68, no. 4 (2014): 400-404.

[13] Nathaniel D. F. Allen, "Unusual Lessons from an Unusual War: Boko Haram and Modern Insurgency," The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 40, no. 4 (2017): 119.

[14] Agbiboa, 404.

[15] Jacob Zenn, "Boko Haram’s factional feuds: internal extremism and external interventions," Terrorism and Political Violence (2019): 1-33.

[16] International Crisis Group, "What role for the Multinational Joint Task Force in fighting Boko Haram?" International Crisis Group Africa Report, No. 291 (2020).

[17] Ibid.

[18] See for example: "Jihadist Attack Kills 13 in Northern Cameroon," Defense Post, January 8, 2021; "Four Chadian Soldiers Killed in Lake Chad Blast," Defense Post, November 25, 2020; "At Least 27 Killed in Niger in Boko Haram Attack," Defense Post, December 14, 2020,

[19] Jacob Zenn, "ISIS in Africa: The Caliphate’s Next Frontier," Center for Global Policy, No. 26 (2020).