Against the background of the deadlock in the peace process and the severe crisis in US-Palestinian relations following US President Donald Trump’s declaration recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel in early December 2017, senior Palestinian officials, including Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas and Secretary-General of the PLO’s Executive Committee Saeb Erekat, said that the Palestinians may withdraw from the two-state solution and seek a one-state solution instead, one that will grant full equality to all citizens. The statements could be interpreted as a tactical step aimed at exerting pressure on Israel, the United States, and the international community to reconfirm their commitment to the two-state solution, and thus bolster the increasingly frayed legitimacy of the Palestinian leadership among the Palestinian public. Alternatively, the declarations, which were accompanied by an announcement that the Palestinians no longer accept the United States as a mediator in the political process, can be interpreted as an attempt to avoid dealing with the peace plan that Trump is expected to announce during the first half of 2018.

Similar statements were already made in the past by Palestinians, including during the negotiations with Israel, but they served as a means of pressure and did not convey a public position on the part of the Palestinian leadership. The current context is different and stems from the Palestinians' sense of strategic distress: an American administration perceived as biased toward Israel and even as hostile to the Palestinians, especially in view of Trump's recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel; an Arab world indifferent to the Palestinian issue, and which has pushed it to the bottom of its agenda; the ongoing erosion of the legitimacy of Abbas and of the Palestinian Authority itself, and as a result, the public's limited willingness to engage in protest and widespread popular resistance; and Egypt’s cooling attitude towards the Palestinian Authority and its leadership, as expressed by the exertion Egyptian pressure on Fatah to adopt Hamas' position in the reconciliation process and to postpone the future status of Hamas' military wing to a later stage.

Also behind these recent declarations is the Palestinian Authority's fear of being held responsible for the failure of the reconciliation process with Hamas, and Abbas's personal fear that the split in the Palestinian camp will be cemented in the Palestinian national consciousness as his legacy. Moreover, the political document published by Hamas in May 2017 expressed willingness to accept a temporary Palestinian state within the 1967 borders, but recognition of Israel was rejected out of hand. In light of the many difficulties involved in ending the decade-long split between Gaza and the West Bank and promoting reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, the one-state solution creates a common denominator for bridging the differences between the two factions. The helplessness of the Palestinian Authority, coupled with Hamas’ distress over its failure to manage the Gaza Strip, is prompting both sides to reconvene around the defining and historic values and symbols of Palestinian nationalism - a Palestinian state from the river to the sea.

Moreover, the call for a single state with equal rights for all its citizens has also received some support in the West when it is presented by the Palestinians as an alternative to the reality of occupation and what they characterize as apartheid. The political declarations in favor of one state express the Palestinian ethos as reflected in PA textbooks and its postage stamps. Both declarations and the accompanying educational messages raise the question of whether the Palestinians have indeed "crossed the Rubicon" and relinquished the narrative of "historic Palestine" in favor of a negotiated settlement for two nation-states.

“One State” as the Palestinian Ethos in Textbooks and Postage Stamps

A review of the current Palestinian discourse and the symbols that appear in textbooks and postage stamps of the Palestinian Authority in recent years indicates that the Palestinian leadership has yet to reach a decisive decision in support of the two-state solution, and may even have distanced itself from it. The vision of Palestine as a single political unit, which extends across the entire territory of Mandatory Palestine, has been renewed and nourished by the Palestinian leadership and public. The Palestinian leadership, led by senior PLO and Fatah officials, makes dual and contradictory statements supporting a continued commitment to the two-state solution on the one hand, and the idea of a single state on the other. Meanwhile the Palestinian Authority works to inculcate the one-state solution as a consensual national ethos using the education system and official expressions of sovereignty such as postage stamps. According to surveys conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PSR), these trends are also reflected in a decline in the Palestinian public's confidence in the feasibility of a two-state solution.[1]

The ethos of a Palestinian state in all of historic Palestine is channelled into a variety of PA social media platforms, and is particularly prominent in the education system. The maps presented in textbooks for history, geography and civics classes, from elementary school and onward attest to this. The map of "Palestine" within its mandatory borders served from the beginning of the Arab-Israeli conflict as an iconic expression of the Arab-Palestinian rejection of Israel's existence and its ultimate demand for the rectification of the historical injustice inherent in its establishment. This symbol reflects the non-recognition of the 1947 UN Partition Plan and the June 4, 1967 lines, which are perceived by the international community as the basis for any future peace agreement and which, until recently, have been presented as such in the official and declared policy of the PLO and the Palestinian Authority.

While Palestinian Authority textbooks in the past decade have been characterized by ambiguity regarding the precise borders of the future Palestinian state (according to the 2010 report of the Knesset’s Information and Research Centre),[2] this is not the case in maps that appear in current Palestinian textbooks. In recent studies published by the IMPACT-SE Centre for the Monitoring of Peace and Tolerance in School Education[3] and the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies,[4] there are many examples of maps presenting the entire territory as "Palestine," including the areas under Israeli control prior to the Six-Day War, and the near total absence of the name “Israel” on any of these maps. Moreover, the discussion of the United Nations partition resolution in text books refers to it as a source of legitimacy for the establishment of a Palestinian state, but ignores the fact that the resolution validated the establishment of two states, Arab and Jewish. In general, and more conspicuously than previous Palestinian curricula, the concept of a “two-state solution” does not appear in textbooks in a positive context, and even the Oslo Accords, which included exchanges of letters of mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO, are either dismissed or not mentioned at all.[5]

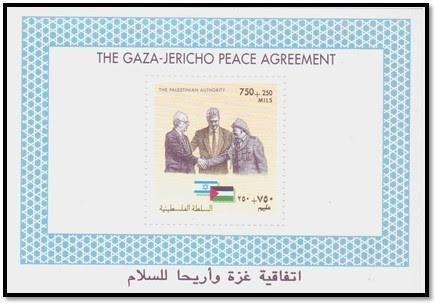

Similar changes were evident in new postage stamps issued by the Palestinian Authority. From the beginning of the independent Palestinian postal service in 1994, relatively moderate images were presented on the PA stamps. For example, in a stamp issued in October 1994 to mark the signing of the Gaza-Jericho Agreement, Israeli and Palestinian leaders and the flags of both countries were presented side by side (Figure 1).

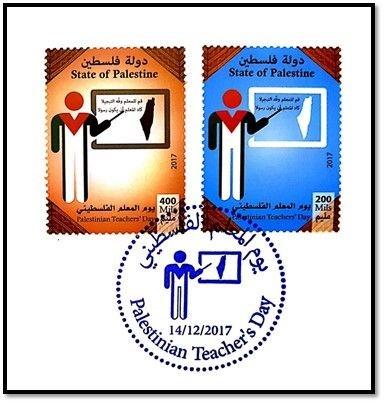

Other recurring images were the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, symbols of folklore and culture, heritage sites, national institutions and leaders. After the Hamas takeover of Gaza, the Palestinian postal system split, and Hamas issued its own stamps that exalted the path of resistance, armed struggle, and jihad. Following the recent Palestinian reconciliation agreement, the Palestinian postal services were to be reunited under the auspices of the Palestinian Authority. In an issue from December 2017, on the occasion of "Palestinian Teacher's Day", the "Palestine" icon, including the entire territory of Mandatory Palestine, appeared on the Authority's stamps for the first time. The new stamps depict a teacher presenting a map on the classroom board showing only one country between the river and the sea - Palestine (Figure 2).

Conclusions

In light of the Palestinian Authority's increasing efforts to instill in its citizens the idea of a "one-state solution," the threat posed by senior members of the Palestinian leadership to withdraw from the two-state solution should not be seen as merely a tactical move. The despair over the failure to achieve the two-state solution during the last quarter-century has contributed to the stubborn refusal of Hamas and significant portions of the Palestinian public to recognize Israel, and provides legitimacy in the Palestinian arena for the revival of the one-state formula as the strategic preference for the Palestinians. The Palestinians’ lack of confidence in leading Arab states' commitment to their cause, and certainly in the fairness of the American mediator, may further strengthen their interest in the one-state formula.

Moreover, it appears that the faltering Palestinian reconciliation process is further hardening views regarding the future. Pragmatic and compromising attitudes are giving way to nationalist and Islamist ideologies, and the prevailing discourse of the mid- nineteen seventies, which emphasised a democratic Palestinian state from the Jordan to the Mediterranean Sea, is likely to serve as the agreed ideological platform between Fatah and Hamas.

The Israeli leadership, for its part, is also pressing the Palestinians to withdraw their support for the two-state solution, by avoiding a clear assertion of its commitment to it, and by its failure to present a clear and reasoned alternative. This policy forces the PA to choose between two alternatives to the existing status quo: a return to violent struggle or non-violent popular resistance in order to revive the two-state solution; or an effort to establish one state that offers equality to all its citizens.

The shifts in the Palestinian discourse, which are backed by the creation of an ethos and narrative and their inculcation, oblige Israel to take seriously the declarations of senior figures in the Palestinian leadership. The positions on the Palestinian side, along with the lack of political readiness and the difficulty in adopting and promoting the two-state solution on the Israeli side, reduce the likelihood of reaching a permanent settlement in the foreseeable future. Moreover, the continuation of the status quo forces the Palestinians into despair, frustration, and anger, and increases the chances of a spontaneous violent eruption that the Palestinian Authority may find difficult to contain.

The future US peace plan (the so-called "ultimate deal") may provide a way out of the impasse and bring a new spirit to the two-state solution, restore both sides' faith in and commitment to it, or lead to a long-term interim arrangement that would allow the establishment of a Palestinian state with provisional borders (PSPB). In the absence of such a plan, Israel will have to consider taking independent steps that will safeguard Israeli security interests, improve the living situation of the Palestinian population, and prepare the ground for a future settlement based on two nation-states.

Kobi Michael is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), and a former Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Strategic Affairs.

Ofir Winter is a Research Fellow at the INSS.

*This article is a translated and edited edition of an article that was originally published in the MDC's Tzomet HaMizrach HaTichon (The Middle East Crossroads) on February 5, 2018. The editorial team at Tel Aviv Notes, would like to thank Tzomet's Editor, Esther Webman, for making the original article available for publication here.

**This article was translated from the Hebrew by Ilai Bavati.

[1] Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, Public Opinion Poll No. 65, October 2, 2017, .

[2] Yuval Vergen, “The Issue of the Contents of Palestinian Textbooks: The Treatment of Jews, Israel, and Peace,” Knesset Research and Information Center, June 30, 2010, See, also: Nathan J. Brown, Palestinian Politics after the Oslo Accords: Resuming Arab Palestine (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2003), pp. 226-227.

[3] Eldad J. Pardo, Arik Agassi, and Marcus Sheff, Reform or Radicalization: PA 2017–18 Curriculum A PRELIMINARY REVIEW, IMPACT-SE (Jerusalem, October 2017).

[4] Arnon Groiss and Roni Shaked, “The Textbooks of the Palestinian Authority (PA): The Attitudes towards Jews, Israel, and Peace,” Studies in Middle East Security No. 141, The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University, December 2017, .