Jordan’s location in the heart of the Middle East, bordering Israel and the Palestinian Territories, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria and nearly Egypt has given it a geopolitical relevance rare for a country of less than 7 million people. With a divided society, split between the monarchy’s traditional source of support, the tribal East Bankers and a Palestinian majority that has been long excluded from political power, and an ever growing number of refugees from neighboring countries, Jordan’s stability has become an important issue in today’s Middle East.

The monarchy has survived the kind of unrest that toppled many regimes in the Arab world. Even though limited and nonviolent protests started early in 2011, when protesters demanded political reform and an end to corruption, calls to depose King Abdullah were rare. In a national address in June 2011, King Abdullah promised a transition to a constitutional monarchy and anti-corruption measures, and has since changed his cabinet five times, created a Constitutional Court and an independent electoral commission; however, the ability to dictate policy has largely remained in his hands, as the parliament plays a largely symbolic role. Elections were held in January 2013, and despite no evidence of corruption, they played into a gerrymandered election system.

The civil war in Syria has led to over 700,000 refugees seeking refuge in Jordan, which, in a country of 6.3 million, amounts to over 10 percent of the population. The influx of Syrian refugees adds to the 400,000 Iraqi refugees during a period in which the country is facing serious challenges, which include stagnant economic growth, high unemployment, and acute current account and budget deficits. These economic issues are accompanied by a growing military threat from the Islamic State (IS), which claims it will target Jordan for participating in the U.S.-led coalition against it.

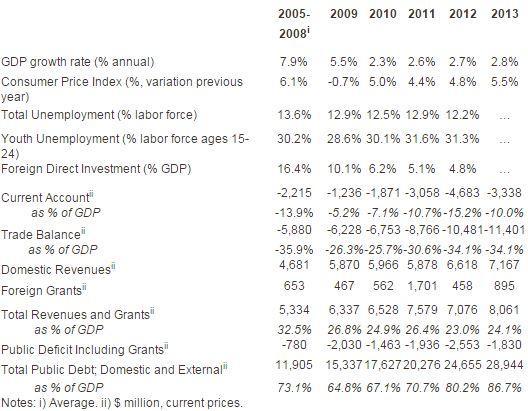

As can be seen in Table 1, Jordan’s annual GDP growth fell from almost 8 percent between 2005 and 2008 to only 2.5 percent between 2010 and 2013. The global financial crisis has affected Jordan since 2009. Foreign direct investment fell from a high of 23.5 percent of GDP in 2006 to 4.8 percent in 2012, largely due to conflict in neighboring countries.

Inflation, measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), averaged 5 percent and unemployment 12.5 percent between 2010 and 2013. Youth unemployment, however, remains high, averaging 31 percent. Persistent unemployment, especially among highly educated youth, is a chronic characteristic of the Jordanian economy.

The current account, a measure of a country’s foreign trade with the world, has been consistently negative since 2005, the same as the trade balance, which is a major component of the current account.

Table 1: Selected Economic Indicators, Jordan 2005-2013

Source: Central Bank of Jordan, except Foreign Direct Investment and Unemployment, which were obtained through the World Development Indicators of The World Bank.

A recent IMF report, [1] measuring the effect of the Syrian crisis on the Jordanian economy, shows that overall growth was 1 percentage point lower in 2013 than its expected level had the Syrian crisis not occurred. In other words, growth in 2013 should have approached 4 percent instead of the actual 3 percent. It also indicates that the influx of Syrian refugees has pushed the prices of non-tradable goods [2] upwards, leading to a CPI 0.6 percentage points higher than it would have been if the Syrian crisis had not happened. The effect on unemployment is debatable because refugees join the informal market, as they are not legally allowed to work in Jordan.

Finally, the report also indicates that the Syrian crisis has taken a toll on Jordan’s trade balance, as major export routes have been affected by the civil war. During the first eleven months of 2013, combined exports to Lebanon, Turkey, and Europe fell by 30 percent compared to the same period in 2012. However the report indicates that the overall effect of this decline on the current account was limited, as there were large financial transfers from abroad that consisted of mainly remittances from Jordanian workers abroad and assistance from foreign governments.

As for public finances, the Jordanian economy is showing signs of strain. Even when including grants from abroad, total revenues are approximately 24 percent of GDP in recent years, while public debt has risen to more than 80 percent of GDP. Even including foreign grants, there has been a persistent public deficit every year since 1998. Indeed grants alone sometimes are not enough, as U.S. and Saudi funds weren’t able to alleviate spiking energy prices in 2012,[3] which forced a $2.05 billion IMF bailout in August of that year.[4] Jordan struggles to collect domestic income and has a very low income tax rate, which ranges from 0 to 14 percent maximum. Jordanian citizens even enjoy a 50 percent tax exemption on annual salaries up to 12,000 Jordanian dinars, or nearly $17,000. This makes a big difference in a country with a per capita income of $5,000.

As the Hashemite monarchy has been ever dependent on foreign aid, and taxation is an eminently political act that requires bargaining with society or civil repression, collecting public revenue by increasing tax rates or decreasing social expenditures that target East Bankers is something that the monarchy has been keen to avoid.

Since 1921 when Abdullah I, with British backing, was appointed the Amir of Transjordan, Jordan has received foreign financial support of various kinds and this has thus become a central feature in Jordanian state-building and contemporary Jordanian politics and society. Historically, most of Jordan’s foreign aid has been funded by the U.S. Between 1957 and 1967, the U.S. provided Jordan with $55 million in combined economic and military aid annually. The amount of U.S. aid spiked after the expulsion of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) in the 1970s, reaching as much as 86 percent of government revenue in 1979.[5] U.S. aid to Jordan expanded again in the 1990s after the peace treaty with Israel and the ascension of King Abdullah II.

Between 1999 and 2013, the U.S. provided over $ 9 billion in economic and military aid to Jordan, and several hundred million more in annual assistance was provided by Britain, the European Union, Canada, and Japan. What’s more, most of the U.S. aid consists of fiscal grants and direct cash transfers rather than soft loans or development assistance. In 2014, the U.S. Congress has appropriated $1 billion in bilateral aid to Jordan, of which $360 million is economic aid, $300 million is military aid, and at least $268 million is designated for the Syrian refugees in Jordan. The U.S. President has already requested over $670 million for Jordan in 2015.[6] During recent years the Arab Gulf States via the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and particularly Saudi Arabia, have provided generous aid to Jordan as well. For example, they donated a $1.4 billion aid package in 2011, and offered the Hashemite Kingdom a subsequent multi-year $5 billion aid package, although this aid is linked to fluctuations of the global oil prices.

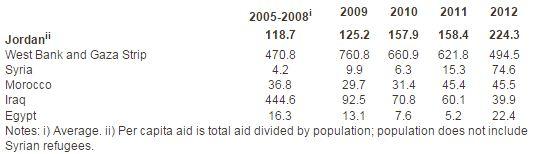

Table 2 shows a comparison of per capita aid and development assistance in the Arab world, which confirms that Jordan is a major recipient, ranking second after the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Aid to Jordan averaged $224 per person in 2012, three times more than Syria and ten times more than Egypt.

Table 2: Official Development and Aid Received, current US$ per capita

Therefore, the huge influx of Syrian refugees into Jordan has come precisely at a time when the Jordanian economy is exhibiting signs of distress. Low growth, unemployment, current account imbalances and a persistent fiscal deficit are a serious threat to the Hashemite Kingdom’s stability. In addition, instability in neighboring states, the remnants of the Arab Spring, and the rise of the Islamic State on its borders also present danger to the current regime.

However, Jordan has managed to remain remarkably stable. One of the most important peculiarities is the vast amount of foreign aid it has received, with a very significant part of it taking the form of direct cash transfers. Nevertheless, the key to its stability might well lie in it East-West bank social-demographic divide: because East Bankers consist of less than 35 percent of the total Jordanian population, they do not support a transition to full democracy, which would inevitably mean the loss of their privileged status under the Hashemite Monarchy. Nor is the Palestinian majority eager to embrace the path to democracy in Jordan, as it has the potential to turn Jordan into a de facto Palestinian State and thus undermine efforts to establish a Palestinian State west of the Jordan River. As long as the majority has reasons to reject full democracy, and as long as international aid continues to flow into Jordan, it is likely that Jordan will remain stable in the years to come.

Dan Poniachik is an intern at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies (MDC). He holds a B.A. degree in Economics from University of Chile.

Notes