Abstract

Scholars have noted that the Druze society has undergone profound and fundamental changes in the modern era. However, most existing research has primarily focused on issues of identity affiliation—Druze, Israeli, Druze-Arab-Israeli, and the like. This article offers a different perspective: rather than addressing declared identity, it focuses on the core of Druze identity—the principle of Brotherly Preservation (ḥifẓ al-ikhwān)—a theological and social tenet that embodies mutual loyalty, communal commitment, and intergenerational solidarity.

The study examined whether this principle, which has served for generations as a central cultural anchor, maintains its stability in the modern era. By comparing different generations within the Druze community in Israel, the study assessed attitudes toward the principle as an indicator of cohesion and communal continuity. The findings revealed no intergenerational differences in attitudes toward Brotherly Preservation—a result that challenges the assumption of a decline in traditional values and instead suggests intergenerational value stability.

The study’s primary contribution lies in the development and validation of a novel empirical questionnaire—the first of its kind—for measuring the principle of Brotherly Preservation. Although designed within the Druze context, this innovative tool may also serve the study of other minority groups concerned with internal communal loyalty, solidarity, and collective identity.

Introduction

The Druze society is one of the most distinctive religious and ethnic groups in the Middle East (Ben-Dor, 1999). It is renowned for its remarkable resilience and its ability to preserve its identity throughout history, despite episodes of persecution and external pressures (Dana, 2003). This regional minority has not only managed to survive but has also played a significant role in both local and regional social and political arenas.

Like all societies, the Druze in Israel are exposed to the realities of modern life and the challenges of the contemporary era. Processes such as globalization, individualization, and modernization (Almog & Almog, 2015) have influenced Druze society just as they have shaped other communities worldwide. The scholarly literature describes a process of identity transformation, in which the younger generation tends to distance itself from traditional values and seeks new identities that integrate modern elements. Previous studies have pointed to conflicts between modernity and tradition, highlighting the growing rift between younger and older generations and their respective inclinations toward individualism. Numerous reports indicate intergenerational tensions and a weakening of norms, social cohesion, and familial bonds within the Druze community. The proliferation of identity affiliations poses a threat to the continuity of the community (Abu Rokon, 2006).

Against this backdrop arises a central question: How does the Druze community continue to endure? Has Druze society in Israel undergone a fundamental transformation such that it differs significantly from its past, or do foundational principles such as ḥifẓ al-ikhwān (Brotherly Preservation) still sustain its social cohesion and ensure its continuity in the modern age?

Conceptual Representation

The original name of the Druze is Muwaḥḥidūn (literally: "those who believe in the One God," i.e., monotheists), and they are also known by the honorific title Banū Maʿrūf (literally: "the people of virtue"). This community comprises approximately two million members worldwide, with major concentrations in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel—countries in which they constitute a religious minority (Zisser, 2015; Hazran, 2014).

The religion of Tawḥīd was propagated between the years 1017 and 1043 and is composed of epistles inspired by Neoplatonic Greek philosophy (Ben-Dor, 1995). Its teachings are documented in al-Ḥikma ("The Book of Wisdom"), which adherents safeguard with great diligence (Armanet, 2018; Makārim, 1974). The Tawḥīd movement was officially established in Egypt in 1017 during the reign of the Fatimid Caliph al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh (“The Ruler by God’s Command”), marking the beginning of a new era. However, following the official closure of the religion to new adherents in 1043, the community became a closed esoteric group. Since then, Druze have refrained from intermarriage with non-members, an act considered a grave transgression (Firro, 2019; Avivie, 2002).

At the outset of the religion’s dissemination, its followers were commanded to uphold preservation and survival principles designed to foster respect for others based on the inner truth of the community—a truth that generates unity and stability, grounded in internal solidarity and the safeguarding of fellow Tawḥīd adherents. This is the principle of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān (“Brotherly Preservation”), a foundational tenet of Druze culture that embodies mutual obligation, loyalty, and intergenerational solidarity.

This principle functions not only as a stabilizing force within Druze society but also as a personal, social, and political behavioral code that guides members of the community in their actions and decision-making (Eilat, 2023; Halabi et al., 2023; Khazran, 2022). ʿAdl al-lisān (“justice of the tongue”), meaning to speak truthfully and pursue justice, is a precondition for fulfilling the commandment of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān, since one who does not speak justly cannot uphold his brother. Falsehood and betrayal undermine both cohesion and the group’s very existence.

This ethos also explains the Druze sensitivity to honor, to promises made (Taqī al-Dīn, 1902/1999), and to covenants formed with others. It is reflected in the Druze community’s active contribution to the state in which they reside, while simultaneously maintaining their internal values (Wahba, 2021).

The principle of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān (Brotherly Preservation) calls for the safeguarding of the well-being and dignity of the Muwaḥḥidūn (monotheistic believers), ensuring their welfare and serving them with pure intentions, without any expectation of reward. According to this principle, an individual’s true wealth is measured by their closeness to the group. The cornerstone of communal security and a fundamental element of Druze unity is the obligation to express solidarity with fellow community members and to act on their behalf when they are in distress or engaged in a just struggle (Taqī al-Dīn, 1902/1999).

The teaching of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān is deeply embedded in the daily life of the Druze and influences all spheres of existence, from the familial and communal to the internal and external policies of the community. Within family and community life, the principle first and foremost manifests in the brotherhood and internal solidarity that characterize Druze society. Caring for the elderly or assisting relatives facing hardship is viewed as a moral obligation directly derived from the principle of Brotherly Preservation.

At the communal level, this principle is expressed through robust social support systems. Community members are expected to help one another in times of need—whether economically, emotionally, or physically. Mutual concern is not only a religious duty but also a social imperative that ensures communal cohesion and the preservation of tradition. This support also takes shape through participation in family and communal ceremonies such as weddings, funerals, and religious events—participation that is regarded as a collective duty and a reflection of shared commitment among members of the community.

A vivid example of this principle in action was the Druze community's response to a dramatic event—the rocket strike on Majdal Shams in July 2024. The principle of Brotherly Preservation was powerfully demonstrated when community members rapidly mobilized to ensure the safety of the town’s residents. The concern and mobilization were evident not only in the participation of thousands in the funeral but also in the coordinated efforts with local authorities and state institutions. The event highlighted the Druze community’s profound sense of collective responsibility and its unwavering commitment to protect the lives of its members, even in times of crisis.

Presentation of the Study: Examining Social Change in Druze Society Through the Principle of Brotherly Preservation

Between January and October 2021, a comprehensive study was conducted to examine the attitudes of Druze citizens in Israel toward the principle of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān (“Brotherly Preservation”) and its implementation in practice. The study focused on an intergenerational comparative analysis of perceptions surrounding this principle, aiming to assess the extent of social change within Druze society.

To this end, a new questionnaire was developed based on a reliable solidarity scale (Bengtson et al., 2002), adapted specifically to suit the study population. The survey sample included 225 Druze participants aged 20 and above, selected from four Druze localities using a cluster sampling method to reflect the community’s social diversity:

- Yanuh, a homogenous Druze village where all residents are Druze;

- Shefa-‘Amr (Shfar’am), a mixed city in which Druze comprise a small minority (14%);

- Majdal Shams, a geographically and socially isolated village in the Golan Heights;

- Daliyat al-Karmel, a locality situated near a major urban center (Haifa).

The selection of these sites was intended to provide a broad and accurate representation of the Druze community.

The statistical analysis compared generational cohorts—from the older and “silent” generation (aged 80 and above) to the younger Generation Z (in their twenties)—and examined the relationship between generational affiliation and attitudes toward the principle of Brotherly Preservation. In addition, a comparative case study approach was used to explore how residential patterns affect sectarian solidarity as expressed through this principle.

The study tested two central hypotheses:

- A negative correlation would be found between respondents’ generational affiliation (age) and their attitudes toward the principle of Brotherly Preservation; that is, the greater the generational gap, the lower the level of agreement on its values.

- Differences would emerge among the case study localities in attitudes toward the principle, with communities in which Druze constitute a minority expected to express greater agreement with the values of Brotherly Preservation compared to those where Druze form the majority.

The importance and contribution of this research stem from the fact that it is the first empirical study of its kind to address a topic that, despite its acknowledged significance in existing literature, has not yet been systematically explored within the Druze community. The study not only deepens our understanding of Druze society, but also offers a new and unique research tool: a measurement scale centered on the principle of Brotherly Preservation. This scale may serve not only in further research on the Druze but also in the study of other minority groups concerned with internal solidarity and collective cohesion.

Research Procedure

The research questionnaire was specifically developed for this study, based on a well-established and reliable instrument (Bengtson et al., 2002; Katz & Lowenstein, 2012; Katz et al., 2015) originally designed to assess intergenerational solidarity within families. For the purposes of this study, the questionnaire was expanded and adapted to examine the principle of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān (Brotherly Preservation) within Druze society.

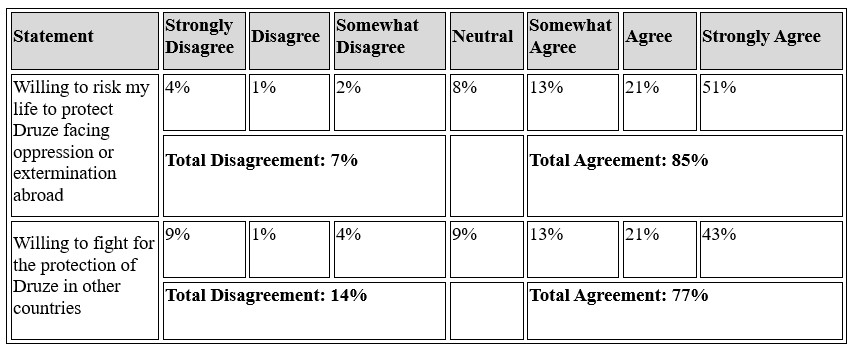

Rather than assessing attitudes alone, the questionnaire also explored participants’ willingness to act—and actions already taken—in support of this principle. Respondents were asked, among other things, about their readiness to provide financial support to community members; to participate in communal activities; to offer political backing; and even, if necessary, to risk their lives to protect Druze individuals in other regions, including those beyond the borders of the state. These items were measured using 26 questions rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from complete agreement (7) to complete disagreement (1), allowing for in-depth analysis of the responses.

The data collection process was both challenging and rewarding. A range of outreach methods was employed to reach as many participants as possible, including distribution of survey links via platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook, email campaigns, random telephone calls, and even face-to-face encounters with participants in marketplaces and sacred sites. All collected data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software.

Research Findings

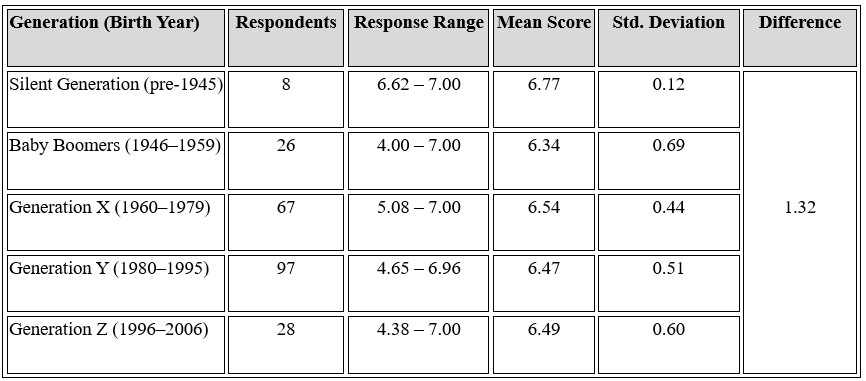

The findings revealed cross-generational conservatism and an absence of intergenerational conflict across all measured dimensions—from the Silent Generation to Generation Z—as shown in Table 1:

No statistically significant differences were found between religious and non-religious participants. The vast majority—both religious and secular—were familiar with the concept of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān and identified with it. Over 90% of respondents expressed willingness to make financial contributions in support of this principle, and 84% stated they would be willing to make a tangible physical contribution, such as organ donation.

The study demonstrated overwhelming agreement with traditional values, including strong attachment to the land and strict adherence to endogamy within the Druze community. An overwhelming 91% agreed that marrying outside the community constitutes a grave, unforgivable offense.

In the political sphere, the research highlighted loyalty to the state as a theological value derived from the religious imperative to speak truth and uphold promises.

Throughout data collection, a strong sense of warmth and communal closeness was observed among participants—even toward strangers. In one instance, a survey participant who was completely unfamiliar with the research team insisted on inviting them for tea and shared thoughts about the significance of Brotherly Preservation in his community. In other cases, individuals expressed genuine joy and willingness to assist, whether by providing information or offering help to others. These examples illustrate how ḥifẓ al-ikhwān is not merely an abstract concept, but a lived value that actively shapes Druze behavior.

Contrary to claims found in earlier literature, the findings of this study indicate that modernization has not led younger generations to abandon traditional Druze values. On the contrary, young people are finding new and modern ways to express their commitment to the principle of Brotherly Preservation. This is evident in their participation in community activities, religious events, and their maintenance of strong familial and social ties—even in the digital age.

With regard to the second hypothesis, the study found that Majdal Shams exhibited significantly more conservative attitudes than the other three localities. A possible explanation draws on conflict theory, which posits that a group tends to cohere and adopt more conservative views when under threat. In this case, the perceived threat stems from the historical context of peace negotiations between Israel and Syria involving the Golan Heights (Inbar, 2011), and more recently, from the Syrian civil war and fears of its potential spillover into the region.

Discussion and Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to examine the relationship between the generational affiliation of Druze respondents in Israel and their attitudes toward the teaching of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān (Brotherly Preservation), as an indicator of intergenerational solidarity. In doing so, the study sought to address the broader question: Has a fundamental transformation occurred within Druze society in Israel?

The findings clearly indicate that there are no significant generational differences in attitudes toward solidarity in Druze society. In this regard, no fundamental change has taken place. This result stands in contrast to existing literature, which often highlights substantial and essential differences between the perceptions of older and younger generations (Lowenstein & Ogg, 2003), as well as intergenerational conflicts over solidarity norms in Western societies (Bengtson et al., 2002; Silverstein et al., 2002; Sellin, 1938).

Furthermore, the findings challenge previous studies on the Druze community that have pointed to generational tensions, identity fragmentation, and rifts between religious and non-religious members—particularly in the context of modernity (Abu Rokon, 2006; Amrani, 2010).

As for the second hypothesis, the finding that Majdal Shams exhibits statistically significant conservative attitudes compared to the other surveyed localities does not align with existing research on Druze minorities surrounded by other dominant ethnic or religious groups (Halabi, 2018). However, this divergence may be explained through conflict theory, which suggests that groups tend to become more cohesive and conservative when under external threat. In this case, the perceived threat arises from past peace negotiations between Israel and Syria involving the Golan Heights (Inbar, 2011), and more recently, from fears linked to the Syrian civil war.

From a theoretical perspective, the study developed and validated a new, Druze-specific questionnaire, which can be adapted for use with other ethnic minority groups. It expands our understanding of Druze society in Israel from a novel angle, revealing that the principle of Brotherly Preservation is not merely a theological or abstract ideal but a practical, lived ethic shared by all generations—young and old alike. While generational gaps exist in certain areas, there remains strong consensus around this value, a surprising yet highly significant finding. It suggests that, despite the sweeping changes occurring in the broader world, Druze society continues to maintain exceptionally high levels of social cohesion.

From a practical standpoint, the study underscores the centrality of ḥifẓ al-ikhwān in Druze society and the widespread consensus surrounding it. This insight is particularly valuable for institutions and agencies that work with the Druze population and seek to support its cultural preservation. It is equally important for Druze community leaders themselves, who are actively engaged in understanding the social dynamics shaping their community and in steering those trends in ways that safeguard their heritage and cohesion.

Shadi Halabi is a doctoral student in the Department of Government and Political Theory at the School of Political Science, University of Haifa, and a research fellow at the Center for Druze Heritage in Israel. His research focuses on the power of non-state actors, transnational solidarity, social capital, power, and conflict.

*This essay is a shortened and edited version of an article originally published in Israel Affairs:

Shadi Halabi, Gabriel Ben-Dor, Peter Silfen & Anan Wahabi (2023). “The ‘preservation of the brethren’ principle among Druze Intergenerational Groups in Israel,” Israel Affairs, 29:5, 931-950.

**The opinions expressed in MDC publications are the authors’ alone.

Bibliography

Armanet, Eléonore. 2018. "‘Allah has spoken to us: we must keep silent.’ In the folds of secrecy, the Holy Book of the Druze." Religion 48 (2): 183-197.

Ben-Dor, Gabriel. 1999. "Minorities in the Middle East: Theory and Practice." In Minorities and the State in the Arab World, edited by Ofra Bengio and Gabriel Ben-Dor, 1-28. Boulder, Colorado & London U.K.: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Bengtson, Vern, Roseann Giarrusso, J. Beth Mabry, and Merril Silverstein. 2002. "Solidarity, Conflict, and Ambivalence: Complementary or Competing Perspectives on Intergenerational Relationships?" Journal of marriage and family 64 (3): 568-576.

Dana, Nissim. 2003. The Druze in the Middle East: their faith, leadership, identity and status. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

Eilat, Omri. 2023. "The Druze Protest in the Summer of 2023." Bayan: The Arabs in Israel.

Firro, Kais. 2019. "Ethnicity, Pluralism, and the State in the Middle East." 185-198. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Halabi, Shadi, Gabriel Ben-Dor, Peter Silfen, and Anan Wahabi. 2023. "The ‘preservation of the brethren’ principle among Druze Intergenerational Groups in Israel." Israel Affairs 29 (5): 931-950.

Halabi, Yakub. 2018. "Minority politics and the social construction of hierarchy: the case of the Druze community." Nations and nationalism 24 (4): 977-997.

Hazran, Yusri. 2014. The Druze community and the Lebanese state : between confrontation and reconciliation. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge : Taylor & Francis Group.

Katz, Ruth, and Ariela Lowenstein. 2012. "Solidarity Between Generations and Elders' Life Satisfaction: Comparing Jews and Arabs in Israel." Journal of Intergenerational relationships 10 (1): 5-21.

Katz, Ruth, Dafna Halperin, Ariela Lowenstein, and Aviad Tur Siani. 2015. "Generational solidarity in Europe and Israel." Canadian journal on aging 34 (3): 342-355.

Lowenstein, A., & Ogg, J. (2003). Oasis: Old age and autonomy: The role of service systems and intergenerational family solidarity: Final report. Haifa.

Makārim, Sāmī Nasīb. 1974. The Druze faith. Delmar, New York: Caravan Books.

Obeid, Anis. 2006. The Druze & their faith in Tawhid. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press.

Sellin, T. (1938). Culture conflict and crime. New York: Social Research Council.

Silverstein, M., Parrott, T., Angelelli, J., & Cook, F. (2002). "Solidarity and tension between age-groups in the United States: Challenge for an aging America in the 21st century." International Journal of Social Welfare, 9(4), 270–284. .

Taqi al-Din, Zayn al-Din Abd al-Ghaffar. 1902\1999. Kitab al-Nuqat wa al-Dawa’ir | The Book of Points and Circles. Edited by Anwar Abi-Khuzam. Beirut: Dar Isharat lil-Tiba‘a wa al-Nashr wa al-Tawzi. The first edition was published in 1902. Seibold, Christian. Leipzig: Max Spirgatis.

Zisser, Eyal. 2015. "The Druze Community and the Lebanese State, between Confrontation and Reconciliation." Bustan: The Middle East Book Review 6 (1-2): 157-161.

אבו רוכון, סועאד. 2006. "הזהות הדרוזית בחברה הישראלית : עדויות מתוך חיי המתבגרים והחינוך למורשת [חיבור לשם קבלת תואר ׳דוקטור לפילוסופיה׳]." החוג לחינוך, חמו"ל.

אביבי, שמעון. 2002. "המדיניות כלפי המגזר הדרוזי בישראל ויישומיה : עקביות ופערים (1948-1967) [חיבור לשם קבלת התואר ׳דוקטור לפילוסופיה׳]." החוג לידיעת ארץ-ישראל, חמו"ל.

אלמוג, עוז ותמר אלמוג. 2015. דור ה-Y בישראל: דוח מחקר. בן שמן: מודן.

אמרני, שוקי. (2010). הדרוזים בין עדה לאום ומדינה. חיפה: קתדרת חייקין לגאואסטרטגיה.

בן-דור, גבריאל. 1995. העדה הדרוזית בישראל בשלהי שנות ה-90. ירושלים: המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה.

והבה, ענאן. 2021. התפיסה המדינית של הדרוזים. בתוך: השבוע במזרח התיכון, עריכה: בוריס גורליק. .

ח׳יזראן, יוסרי. 2022. "ההתקוממות העממית בסוריה ודעיכת המיעוטים - המקרה הדרוזי." אל-דרזיה.