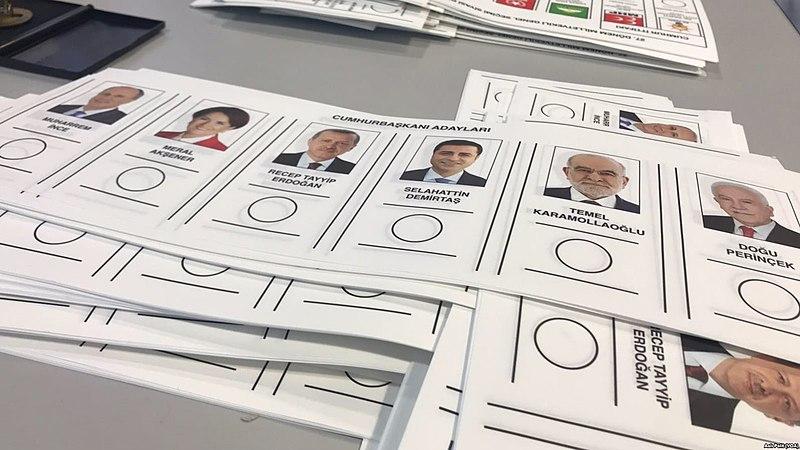

After a tough campaign during which President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s opponents provided a surprisingly stiff challenge to his fifteen-year-long control over Turkey’s government, Erdoğan won re-election on June 24.[1] His Justice and Development (AKP) party, in coalition with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), cemented his success by winning over 50 percent of the seats in Parliament. Some Turkish politicians and journalists have claimed the elections were unfair given both the media’s disproportionate coverage of Erdoğan’s rallies during the campaign and allegations of voter intimidation and ballot stuffing on election day.[2] However, Erdoğan’s main opponent, Muharrem İnce, accepted the election’s results and conceded defeat.[3] The 2018 elections appear to be a watershed moment for Erdoğan: he won the presidency, his coalition gained a majority in the Parliament, and he is stepping into a new presidential system that grants the executive unprecedented new powers. The significance of this victory is bolstered by the fact that anticipated checks on Erdoğan’s power given the MHP’s large contribution to the Parliamentary majority have not materialized. However, Erdoğan’s victory is not as all-encompassing as it might seem. The AKP’s failure to attract new voters and Turkey’s deteriorating economy pose serious challenges for Erdoğan’s new government.

A number of analysts claim this election marks a new stage in Turkish politics where Erdoğan’s authoritarian style is institutionalized by law.[4] Erdoğan’s authoritarian turn can be traced back to 2013, when Erdoğan’s former political ally, the influential Islamist leader Fethullah Gülen, was believed to have leaked videos implicating Erdoğan and other AKP officials in widespread corruption. Erdoğan responded by dismissing thousands of police officers, prosecutors, and judges, and targeting all Gülenists (whom the government now regards as terrorists). After a failed coup in the summer of 2016, Erdoğan grew even more authoritarian. According to conflicting reports about the coup, members of the Turkish army attempted to oust Erdoğan. The coup failed—Turkish citizens, loyalist soldiers, and police went into the streets and reversed the coup within a few hours—but it left a large imprint on Erdoğan and his rule.[5] In the coup’s aftermath, Erdoğan imposed a state of emergency on Turkey. Under the guise of this state of emergency, Erdogan passed hundreds of decree laws, many of which constituted a newfound assault on Gülenists, who the government sees as responsible for the coup. Other decree laws, however, departed from issues relating to the coup, legislating on civil or economic matters.[6] Under emergency rule, Erdoğan also conducted a massive crackdown on journalists, imprisoning hundreds and leading to Turkey becoming known as the “world’s worst jailer for journalists.”[7]

Erdoğan’s actions under the state of emergency led many international politicians and organizations to accuse him of being an authoritarian ruler.[8] These claims were strengthened by Erdoğan’s 2017 referendum that changed Turkey’s governing model from a parliamentary system to an executive presidency. In a closely-contested vote (whose results, in many ways, foreshadowed those of the 2018 elections), a “Yes” bloc formed by the AKP and the MHP secured a slim victory with 51.4 percent of the votes. The new system—which was officially inaugurated by the June 2018 elections—enshrines the president’s ability to appoint members of the judiciary branch without oversight from Parliament, to issue decrees (not only in Emergency Law situations), and to issue budgets for the Parliament’s approval.[9] The system also eliminates the role of the Prime Minister, and it allows the President to choose members of his Cabinet from outside of the Parliament.

After the presidential referendum, the Turkish parliament under Erdoğan’s leadership changed Turkey’s electoral law. The legislation included provisions that allowed parties to run for Parliament together in a coalition, that allowed ballots that are not stamped by election officials to be counted, and that enabled the Supreme Electoral Council to redraw voting districts and move ballot boxes for security reasons.[10] Around a month after the legislation passed, Erdoğan and MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli announced that the next elections would be moved forward to June 2018, eighteen months earlier than scheduled. In opposition to his long-standing contempt for early elections, Erdoğan explained that the early elections were necessary in order to expedite the transition into the new presidential system. Analysts, however, attributed the earlier election date to increasing woes about the country’s economy and the Syrian war, explaining that Erdoğan and Bahçeli thought their prospects were stronger now than they would be in 2019.[11]

Given the election’s results, it seems that Erdoğan and Bahçeli calculated correctly. The AKP-MHP coalition elected Erdoğan and won a comfortable majority of 53.7 percent in Parliament, coming out nearly 20 percentage points ahead of the coalition led by the second-largest party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP). Much of the coalition’s success can be attributed to the MHP’s large contribution: it won 11.1 percent of parliamentary votes, a bit over one-quarter of the 42.6 percent the AKP received. This result defied predictions because many expected that Bahçeli’s unpopularity and the presence of the Good Party, which split off from the MHP once it began cooperating with Erdoğan, would lead to a diminished voter base for the MHP.[12] The Good Party’s center-right, nationalist, and anti-Erdoğan stance was expected to appeal to AKP voters who were fed up with Erdoğan. However, the MHP overcame these obstacles, gaining only 0.8 percent fewer votes than it did in the 2015 Parliamentary elections. Amidst accusations that this result was fraudulent, analysts have offered various explanations for the MHP’s success. Some argue that disgruntled AKP supporters who wanted to express their dissatisfaction with Erdoğan but did not want to move to the CHP-led bloc (which the Good Party was a part of) switched to the MHP.[13] Others point to the MHP’s success in Kurdish regions.[14] Journalists attribute the rise in support from Kurdish regions to the increased number of MHP-leaning government personnel, soldiers, and security guards in these regions, as well as to intimidation facing voters for the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP).[15] Furthermore, because the MHP voter share increased most noticeably in municipalities where Kurdish elected officials had been deposed and AKP-appointed officials had been placed, some explain that the new local governors convinced their employees to vote for the MHP in exchange for job security.[16] In addition, anti-Syrian sentiment and the breakdown of Erdoğan’s 2015 peace process with the Kurds have led to an overall increase in nationalistic sentiment; this wave of nationalism enabled both the Good Party and the MHP to win enough votes to pass the 10 percent threshold needed to enter in Parliament.[17]

It is unclear, however, whether the MHP’s contribution to the coalition’s Parliamentary majority will translate into increased influence over the AKP. In the immediate aftermath of the elections, some predicted that because Erdoğan needs to retain a majority in Parliament, he would accede to MHP demands and shift to a more nationalistic agenda, including continuing to crack down on the Kurds. Bahçeli, according to some reports, was pushing for Cabinet positions for himself and other MHP officials.[18] However, Erdoğan did not appoint any MHP ministers to his Cabinet, and while Erdoğan has issued decrees that change Turkey’s security establishment, these changes are intended to consolidate executive power and do not reflect MHP influence.[19] In addition, a closer look at parliamentary dynamics, coupled with Erdoğan’s historic unwillingness to be beholden to others, suggests that it is unlikely that Erdoğan will accommodate an independent MHP agenda. The AKP holds 295 seats in Parliament, only six below a Parliamentary majority. Erdoğan is not desperate for these six votes—if the MHP is overly demanding, he could turn to the Good Party, or, rather than being chained to the MHP or the Good Party, the AKP could simply assume that six deputies would be open to working with the AKP on particular pieces of legislation.[20] Thus, while retaining a parliamentary majority is not trivial—the Parliament holds powers include enacting, amending, and repealing laws, deciding to issue currency and declare war, and approving the ratification of international treaties—it is unlikely that Erdoğan will be held hostage to MHP demands.

While the MHP may not pose an immediate threat to Erdoğan’s power, challenges to the continued success of the AKP loom in the future. An analysis of electoral dynamics in Turkey reveals that Erdoğan’s support base is not as unchallengeable as the party’s record suggests. In this election, Erdoğan received 26.3 million votes for President while the AKP received 21.3 million votes, indicating that Erdoğan relied on MHP voters to secure his victory. Furthermore, in Presidential elections in August 2014, Erdoğan received a similar 21 million votes.[21] When assuming that the voters for AKP in this election constitute the same segment of Turkish voters as the ones who voted for Erdoğan (when he was running without a coalition) in 2014, it seems that Erdoğan’s voter base has remained stable: around 21 million people voted for him in both elections. However, in 2014 Erdoğan’s 21 million voters constituted 51.8 percent of the voting electorate, while in 2018 Erdoğan’s 21.3 million voters only constituted 42.6 percent of the total.

Erdoğan, then, seems to be failing to attract new voters or, if he is, he is only breaking even with the voters he is losing. Though Erdoğan’s supporters are loyal, this loyal base has not expanded much in the last four years, even though Erdoğan has implemented changes to Turkey’s education system that one might predict would lead to a population of new voters that ideologically aligns itself with him.[22] Erdoğan himself seems to be aware of his predicament. After elections, Erdoğan said: “We have received the message from our nation. Rest assured, in the next term we will make up for all our shortcomings.” Erdoğan understands that while he won this election, his party’s performance was disappointing, and that he must address the present “shortcomings” to ensure his future success.

While Erdoğan did not delve into what these shortcomings are, one can reasonably assume that he was alluding—at least in part—to Turkey’s economy, which has considerably weakened in the past few years. The current Turkish economic crisis is particularly dangerous for Erdoğan because much of his prior success was tied to Turkey’s economic success. In a summary of Erdoğan’s life and his accomplishments on the Turkish government’s website, his economic reforms are emphasized. The site mentions that as Prime Minister, Erdoğan curbed inflation that had been plaguing the country for decades, that he lowered the rate of the state’s debt interests, and that he considerably increased the national income per capita.[23] The Turkish economy indeed flourished under Erdoğan’s rule—between 2002 and 2012, the Turkey’s gross domestic product increased by 63 percent, and in 2013, Turkey was the world’s 18th-largest economy.[24]

However, as Erdoğan’s policies have become increasingly authoritarian—including his efforts to curtail the Turkish Central Bank’s independence—the economy has struggled. During April-May 2018, the Turkish lira fell 24 percent against the dollar.[25] The Turkish economy is plagued by an overreliance on domestic demand and a growing account deficit. To relieve these factors, economists argue that the AKP needs to follow a more conventional monetary policy, which would include restoring the Central Bank’s independence so that it can reach its inflation target.[26] While many hoped that with an AKP victory, Erdoğan would abandon his unorthodox economic belief that high interest rates increase inflation, he has since done the opposite. Erdoğan’s statements that interest rates would fall and his appointment of his son-in-law Berat Albayrak (who many see as Erdoğan’s eventual successor) to head the economy as the Minister of Finance and Treasury have been disastrous for the lira; it hit a record low on July 12 after falling 6 percent in the week following Albayrak’s appointment.[27] Given Turkey’s current massive current account deficit, the economy needs a steady flow of foreign investment. Yet Bloomberg columnist Marcus Ashworth wrote that Turkey’s economy is “uninvestable” and argued that it is “dreamland economics to think that the new administration can lower interest rates and inflation, while boosting the lira.”[28] How this seemingly inevitable economic crisis unfolds could deeply damage Erdoğan’s legacy and his popularity.

Thus, while this election was a significant victory for Erdoğan, his success should not be overstated. Erdoğan is facing two interrelated challenges: a voter base that has failed to expand in the last few years and an economy that has been sliding without signs of rehabilitation. While Erdoğan is armed with greater powers as the head of Turkey’s new presidential system, it does not appear that smooth sailing lies ahead for his new government.

Ariella Kahan is the 2018 recipient of the AMISTAU fellowship at the Moshe Dayan Center (MDC) for Middle Eastern and African Studies, Tel Aviv University. She is a rising junior at Harvard College studying History and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations.

[1] See: Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak, “Turkey’s One Man Show,” Turkeyscope, July 15, 2018.

[2] “International Election Observation Mission,” Office for Security and Cooperation in Europe, June 24, 2018; Angela Dewan and Hannah Ritchie, “Erdogan won the elections after an unequal battle, monitors say,”CNN, June 25, 2018; Ece Toksabay and Ali Kucukgocmen, “Erdogan’s election rivals struggle to be heard in Turkey’s media,” Reuters, June 20, 2018.

[3] Amberin Zaman, “What’s next for Turkey’s future following Erdoğan’s election win?,” al-Monitor, June 25, 2018.

[4] Amberin Zaman, “What’s next for Turkey’s future following Erdoğan’s election win?,” al-Monitor, June 25, 2018; Murat Yetkin, “A snap analysis of Turkey’s snap election,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 25, 2018; Zvi Bar’el, “Turkey Elections: Erdogan’s Win Paves Road Toward Autocracy,” Haaretz, June 25, 2018.

[5] “Turkey’s Failed Coup Attempt: All you need to know,” Al Jazeera, July 15, 2017.

[6] Serkan Demirtas, “Emergency rule should not be Turkey’s new normal,” Hurriyet Daily News, January 3, 2018.

[7] “Turkey worst in world for jailed journalists for second year: CPJ report,” Hurriyet Daily News, December 14, 2017; Amberin Zaman, “Will pro-Erdogan journalists join ranks of jailed Turkish journalists?,” al-Monitor, June 13, 2018.

[8] Steven Cook, “How Erdogan Made Turkey Authoritarian Again,” The Atlantic, July 21, 2016; Arthur Beesley, “Alarm raised on Turkey’s drift into authoritarianism,” Financial Times, March 8, 2017; “Turkish government extends state of emergency for another 3 months,” Reuters, July 17, 2017.

[9] “Turkey approves presidential system in right referendum,” Hurriyet Daily News, April 16, 2017.

[10] Ayla Kean Yackley, “Turkey changes electoral law in boost for ruling party,” al-Monitor, March 15, 2018.

[11] Umut Uras, “Turkey: Why did Erdogan Call Early Elections?,” Al-Jazeera, June 4, 2018.

[12] Alex MacDonald, “Dashed hopes and surprise wins mark Turkish elections,” Middle East Eye, June 25, 2018; Sedat Ergin, “MHP was the ‘deep wave’ in Turkey’s election,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 26, 2018.

[13] Barcin Yinanc, “Votes shifted between AKP and MHP, says top pollster,” Hurriyet Daily News, July 2, 2018.

[14] Amberin Zaman, “What’s next for Turkey’s future following Erdoğan’s election win?,” al-Monitor, June 25, 2018.

[15] Pinar Tremblay, “Why ultra-nationalists exceeded expectations in Turkey’s elections,” al-Monitor, June 28, 2018.

[16] Pinar Tremblay, “Why ultra-nationalists exceeded expectations in Turkey’s elections,” al-Monitor, June 28, 2018.

[17] Pinar Tremblay, “Why ultra-nationalists exceeded expectations in Turkey’s elections,” al-Monitor, June 28, 2018.

[18] Amberin Zaman, “More of the same? Erdogan rule to replace emergency rule in Turkey,” al-Monitor, June 28, 2018.

[19] Ece Goksedof, “A close look at Turkey’s new cabinet,” Middle East Eye, July 10, 2018; Metin Gurcan, “Erdogan makes major security changes as he starts new term,” al-Monitor, July 17, 2018.

[20] Murat Yetkin, “The new Turkey: Is Erdogan chained to the nationalist MHP?,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 28, 2018.

[21] Sedat Ergin, “What did Erdogan mean when he said ‘message received’ after the election?,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 27, 2018.

[22] Svante Cornell, “Headed East: Turkey’s Education System,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, March 21, 2018.

[24] Paul Rivlin, “Why is Turkey’s Economy Sliding Again?,” Iqtisadi, February 23, 2014; Paul Rivlin, “Turkey’s Pre-Election Economic Crisis,” Iqtisadi, June 17, 2018.

[25] Paul Rivlin, “Turkey’s Pre-Election Economic Crisis,” Iqtisadi, June 17, 2018.

[26] Paul Rivlin, “Turkey’s Pre-Election Economic Crisis,” Iqtisadi, June 17, 2018.

[27] Ayla Jean Yackley, “Turkey’s Battered Lira Takes Another Hit,” al-Monitor, July 12, 2018.

[28] Marcus Ashworth, “Erdogan Risks a $163 Billion Bout of Market Nausea,” Bloomberg, July 12, 2018; Marcus Ashworth, “Erdogan’s New Dynasty Makes the Turkish Economy Uninvestable,” Bloomberg, July 10, 2018.