Introduction

According to 2017 figures provided by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, the adult Arab population in Israel (aged 18 and above) is comprised of 1.1 million individuals, of which young adults between the ages of 18 to 29 constitute 390,000. Their share in the general Arab population is 21%, and their share in the adult Arab population (that is, individuals over the age of 18) is 36%.[1]

The following article examines political and social attitudes of young Arab adults in Israel as they are reflected by a survey conducted by the Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation in August 2017. The survey was based on a representative sample of the adult Arab population in Israel (aged 18 and above) which included 876 respondents, all of whom hold Israeli citizenship. The representative sample of young adults aged 18 to 29 included 312 respondents (48% male and 52% female), which represents 35.6% of the sample population.[2] The sampling error was 2.25%.

Young Arab Adults in Israel: A Social Profile

In the not-so-distant future, the members of the younger generation will shape the face of Arab society. However today, they are in a period of transition in their lives, at the very beginning of their personal and professional development. Born in the 1990s, young Arab adults grew up in an Israeli reality – one of accelerated modernization, increased consumer culture, and the development of an affluent society that identifies with the values of self-actualization and meeting individual desires. In recent years, an Arab middle class whose consumer habits are similar to those of the Jewish middle class has emerged.[3] The increase in marriage age and the amount of unmarried young adults in Arab society shows that many members of the young generation (men and women alike) prefer to first realize their personal aspirations – for example, obtaining higher education or vocational training – before establishing a family.

The influence of the internet and Facebook revolution in Arab society is felt mainly among the younger generation. The findings of a survey conducted by the Israel Internet Society in the summer of 2016 revealed that there is no digital gap between Arab and Jewish young adults; almost all Arabs aged 18 to 29 own smartphones (98%) and use the internet (97%). The majority of young Arab adults use the internet as a source of news and information (90%), and most (64%) are open to receiving information in any language, with no preference for Arabic or Hebrew. [4]

Nevertheless, the younger generation faces difficult challenges. The youngest of them, who are in their early twenties, are high school graduates who have just completed their studies; they are taking their first step into the adult world, looking for entry into the job market or institutions of higher education. A considerable number of young adults find it difficult to integrate into these frameworks and are thrown into a situation defined in professional literature as “inactive,” or NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training). It’s important to note that quite a few of Israel’s young adults (28%), both Arab and Jewish alike are categorized as inactive, however the phenomenon is much more prevalent among Arab youth. Half of inactive young adults are in this status by choice (for example, young women who have finished high school, married, and became house wives), while the other half has not succeeded to integrate into the work force in spite their best efforts.[5] Those who succeed in integrating into the job market still face difficulties in blending in to the world beyond the localities in which they were raised. Many experience palpable culture shock from moving to large cities, from daily friction with the Jewish majority, and from life in a world where Hebrew language and culture are dominant. [6]

The influence of the political environment must also be taken into account. Young Arab adults - and to an even greater extent than most of the Arab population – are affected by the internal political upheavals in Israel and by crises in Israeli-Palestinian relations. Today’s young Arabs grew up in the shadow of the events of the Second Intifada that erupted in September 2000. To this we must add the changes taking place across the Middle East in recent years. The central lesson of the events of the “Arab Spring” in neighboring Arab states was to demonstrate the great power of cohesive groups of young people to initiate change. It’s unsurprising that just like in the surrounding Arab world, many young Arabs within Israel have gravitated toward the local branch of al-Hirak a-Shababi (“The Youth Movement”), an amorphous and unorganized body with no clear political orientation, that is however unique in its unification of young people in their twenties through social media. The movement’s activities are felt in times of collective protest, for example, during the week of protest events that took place in Arab localities over the issue of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in October 2015. Many Arab youths went out to show their presence following encouragement by social media activity affiliated with al-Hirak al-Shababi. [7] Another recent example is the protest that took place in mid-May in Haifa, which was organized in response to the outburst of violence on the Gaza Strip border. Through the initiative of al-Hirak al-Shababi activists, dozens of young Arabs took to the streets to express solidarity with the suffering of Palestinians in Gaza.[8]

Survey Findings

The survey divides the group of 18 to 29-year-olds into two sub-groups: youths aged 18 to 22 and older young adults, aged 23 to 29. Each of the groups has a different social profile. Members of the 18 to 22 age group generally take their first steps in the education or employment world after completing their high school education, while some, mainly Druze men, serve in the army. In general, individuals aged 18 to 22 have not fully disengaged from their parents’ home. As such, their integration into Israeli society is only partial. Conversely, the group of young people aged 23 to 29 have already integrated into the spheres of employment or higher education and are in the process of establishing their own families. Their integration in to the fabric of Israeli life is more advanced than their younger counterparts. According to the survey data, 69% of the respondents in the age group from 18 to 22 are single and only 24% are married (some of which are parents of children). In the older age group (age 23 to 29), most of the participants (55%) are married (half with children and half without) and the percentage of singles is 40%.

The differences between the two groups are not only demographic. The findings of the survey indicate a significant discrepancy in the viewpoints held by the two groups, and some cases wherein their viewpoints are mirror images. As a rule, the group of youths aged 18 to 22 tend to adopt a more pessimistic stance on their experience of life in Israel and they are more critical of state authorities. They tend to place emphasis on their national identity without regard to civic identity. On the other hand, the group of young adults aged 23 to 29 hold less critical views and tend to have measured view of their lives in Israel. They define their identities in both nationalistic and civic terms.

The viewpoints of the respondents were divided into three main fields: (1) Daily life in Israel and personal feelings; (2) Political views; and (3) Definition of self-identity.

General Attitudes and Daily Life

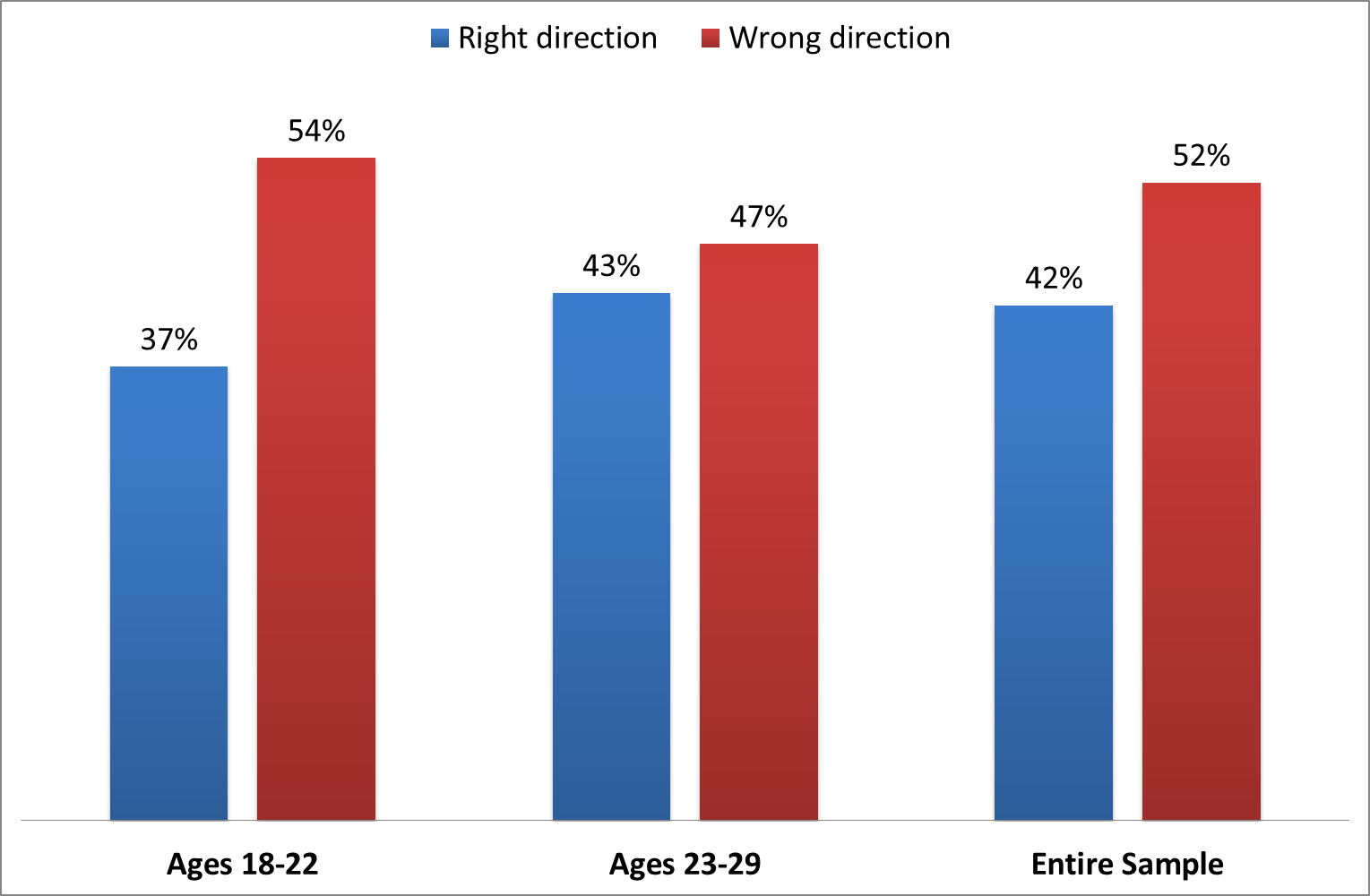

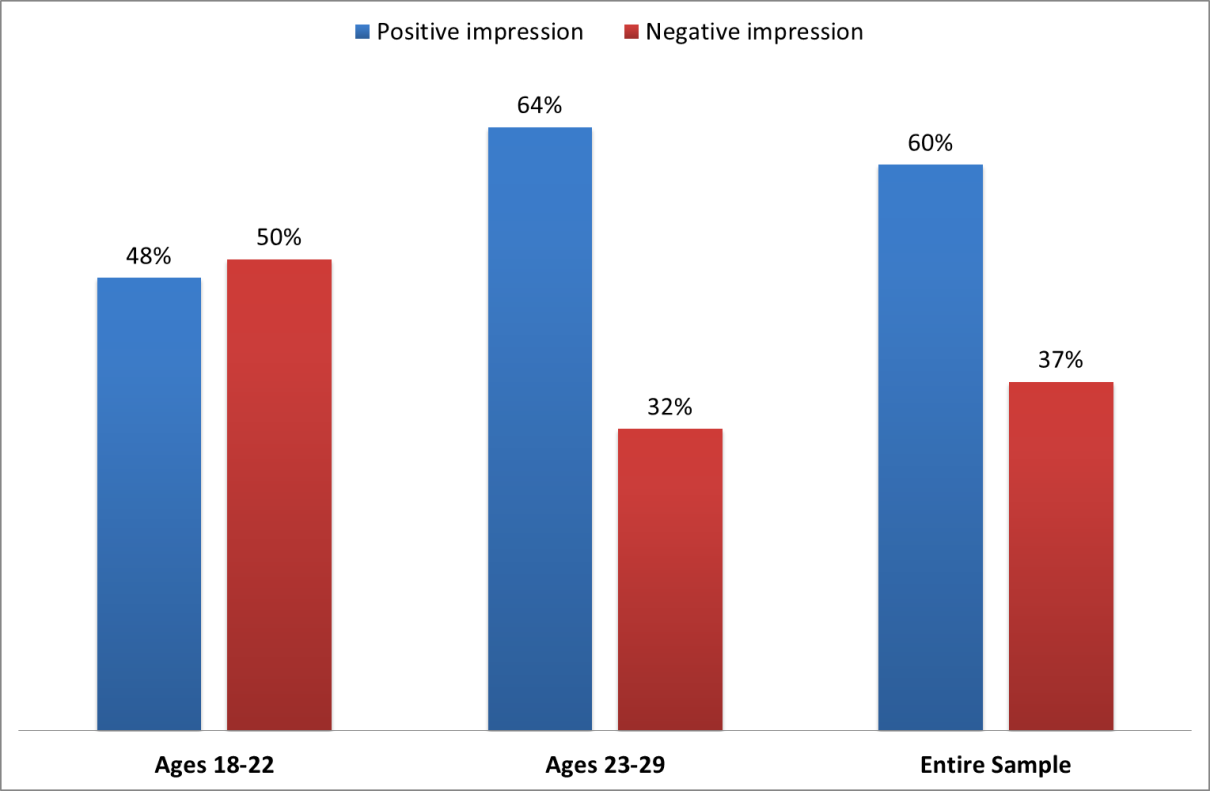

The survey opened by putting a general question to the respondents: “Is Israel going in the right direction or the wrong direction?” The answers of young adults indicated that their attitudes are on par with the general average in the sample population, however the criticism of youths aged 18 to 22 is harsher than the total sample, whereas young adults aged 23 to 29 hold more balanced positions (Figure 1). The picture began to change when respondents were asked to define their general impression of the state (Figure 2). At this point, a mirror image between the two sub-groups is revealed: the younger group (aged 18 to 22) is divided on the question, and the older young adults (aged 23 to 29) mostly report (64%) a positive impression of the state. Their attitude is even more positive than the general average of the sample, in which 60% reported a positive impression of the state.

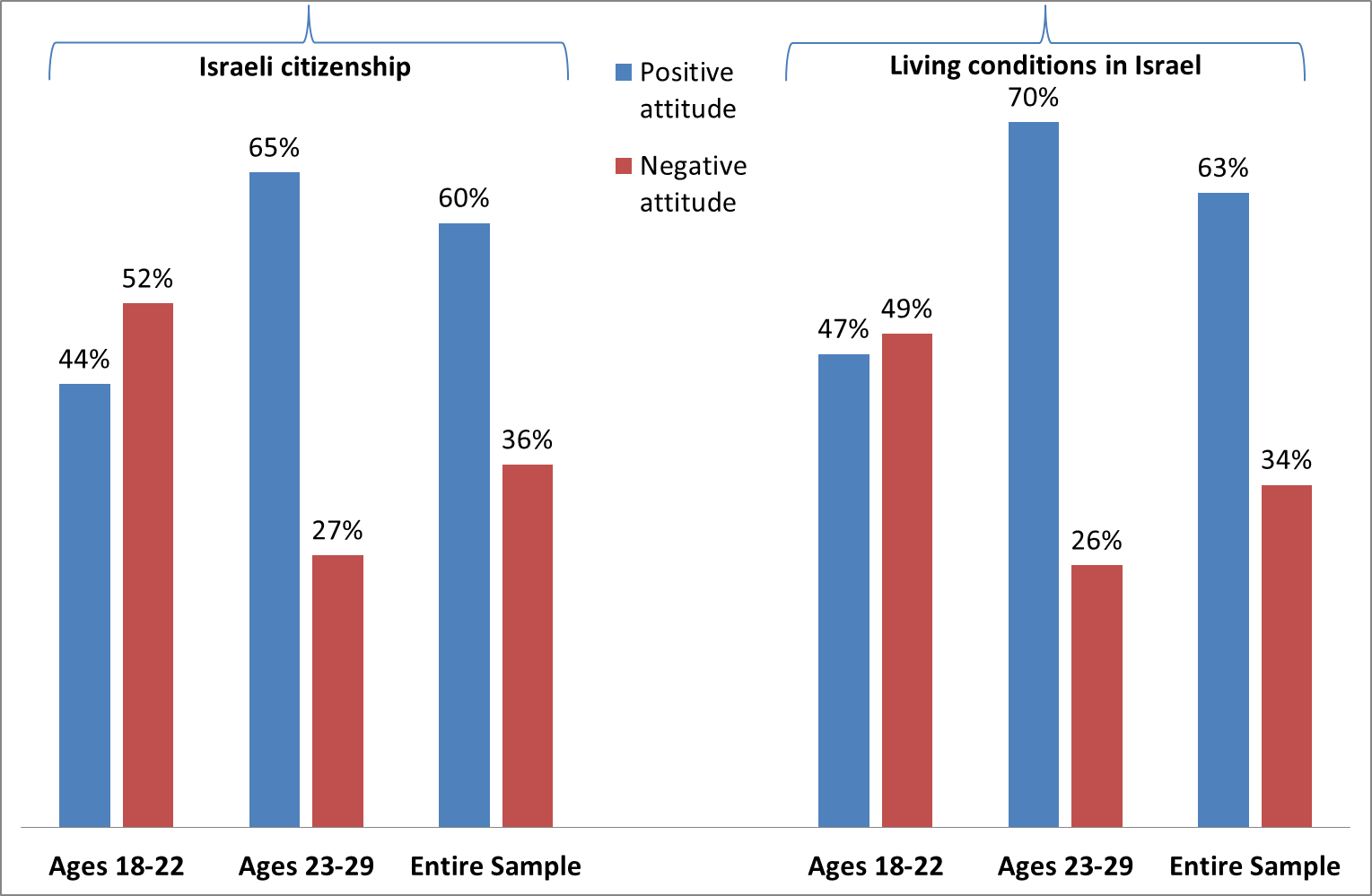

The participants were also asked to answer more concrete questions that express their personal feelings regarding Israeli citizenship and living conditions in the state (Figure 3). The younger group is highly critical of Israeli citizenship, and the majority (52%) expressed a negative attitude toward it. In comparison, the older group, like the general sample, mainly holds positive views toward Israeli citizenship (65%). One possible explanation for the variance in attitudes between the two age groups in that the younger group is taking its first steps in the world of Israeli civic life. Although they are able to participate in Knesset elections for the first time, they generally do not consider citizenship beneficial to them. In contrast, the older group has already integrated into the Israeli experience – including into the job market and into institutions of higher education – and therefore their esteem of Israeli citizenship is greater.

The experience of life in Israel is portrayed in a more positive light. The stance of youths aged 18 to 22 is balanced between those who view the experience of life in Israel positively (47%) and those who see it in a negative light (49%). Among the older age group, a clear majority (70%) hold a positive view towards the living conditions in Israel.

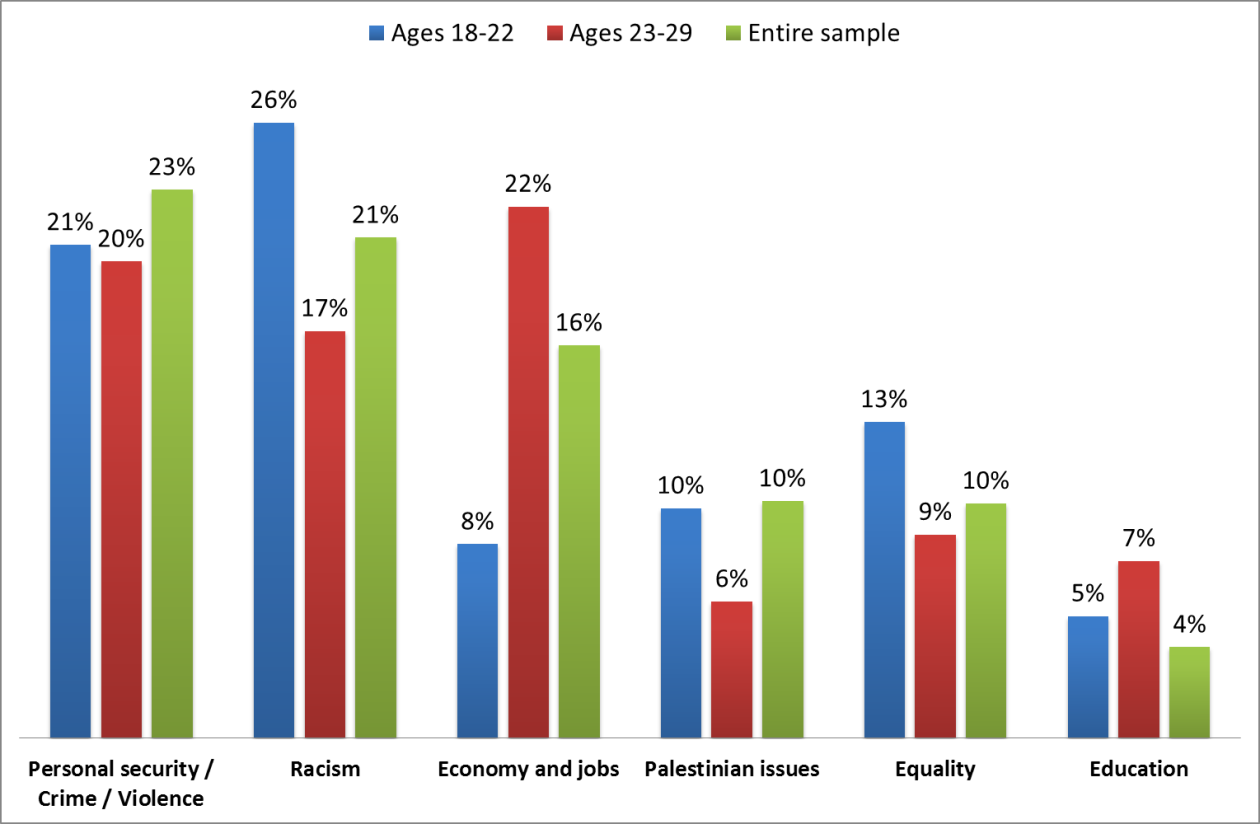

The respondents were asked what issues concern them most in their daily lives. They were presented with a variety of categories in random order and asked to choose the category that most concerns them and their family (Figure 4). From all the respondents’ answers, three categories emerge as the greatest concerns of Arab society: violence and crime (23%), racism (21%), and economy and jobs (16%). These issues also worry the young adult population, but in different order. Racism on the part of the Jewish majority it the most bothersome issue (26%) for Arab youths aged 18 to 22, while Arabs aged 23 to 29 are most bothered by problems of economy and jobs (22%).

These answers illustrate the various challenges that each age group faces. The fact that a quarter of the youngest age group ranks racism as their most significant problem attests to the culture shock they experience following their first direct encounter with Jewish society. In contrast, the older age group, who are in the midst of the process of integration into the Israeli employment market alongside establishing themselves and their own families, are more concerned about problems related to the economy and employment.

Political Views

The participants were presented with several possibilities regarding the political participation of Arab parties in Israel as well as the possibility of an Arab party joining any government in the future. More than one-third of all respondents (36.5%) expressed opposition to joining the government. The attitudes of young Arabs are consistent with this position: the percentage of young people aged 18 to 22 who answered that an Arab party should not join a government coalition was 35.3%, and the percentage of young people aged 23 to 29 who gave the same response was 35.2%. An interesting position emerges from the responses of 18 to 22-year-olds: an especially high percentage of them (37.5%) believe that an Arab party should join the government in the right circumstances. This percentage is higher than the percentage of respondents who agree with this claim of any other age group in the sample. Conversely, it is noteworthy that more than a quarter of participants aged 23 to 29 (26.7%) stated that they had no position on the issue or refused to answer the question.

This finding shows that among young people there is a growing desire to influence what is happening in the country and to bring about political change. This aspiration is nourished by the establishment of the Joint List on the eve of the elections to the 20th Knesset and speaks to the many hopes that the young generation in Arab society has hung upon it. However, the survey findings show that such hopes decline with age. Disillusionment causes a considerable number of young people to "sit on the fence" - to continue to participate in the political game but not to take a clear stance toward the goals of the game for the Arab public.

The respondents were asked about their attitudes towards a series of state institutions: the Knesset, local authorities, the Supreme Court, the government, the prime minister, the office of the president, the army, and the police (Table 2). Segmenting the answers reveals clear differences of opinion between the two age groups of young adults: the younger group harshly criticizes the state's representative institutions - more than half hold a negative view of the Knesset, the government, the Supreme Court and the presidency. On the other hand, the older group is more moderate in its criticism of the Knesset and the government, and even express positive attitudes toward the Supreme Court and the presidency. A mirror image of the attitudes of the two age groups is also evident in relation to security forces (the IDF and the police). More than half of young people aged 18 to 22 hold a negative view of these entities, while half of respondents aged 23 to 29 hold positive opinions of them.

The mistrust of government amongst 18 to 22-year-olds is also evident in their responses to the government's economic development policy. In December 2015, the Israeli government adopted Resolution 922 and approved a budget of 15 billion shekels (over five years) for the economic and social development of Arab communities in various sectors: education, infrastructure, housing, employment, transportation, internal security, and culture. The respondents’ answers revealed that not only had half of the 18 to 22-year-olds never heard of the program (and only a quarter had heard of it), but that an especially high percentage (18%) did not believe that such a program exists. In comparison, amongst 23 to 29-year-olds, the percentage of people who had heard of the program was equal to the percentage of those who had not, and only a small percentage do not believe that the program exists.

Defining Self-Identity

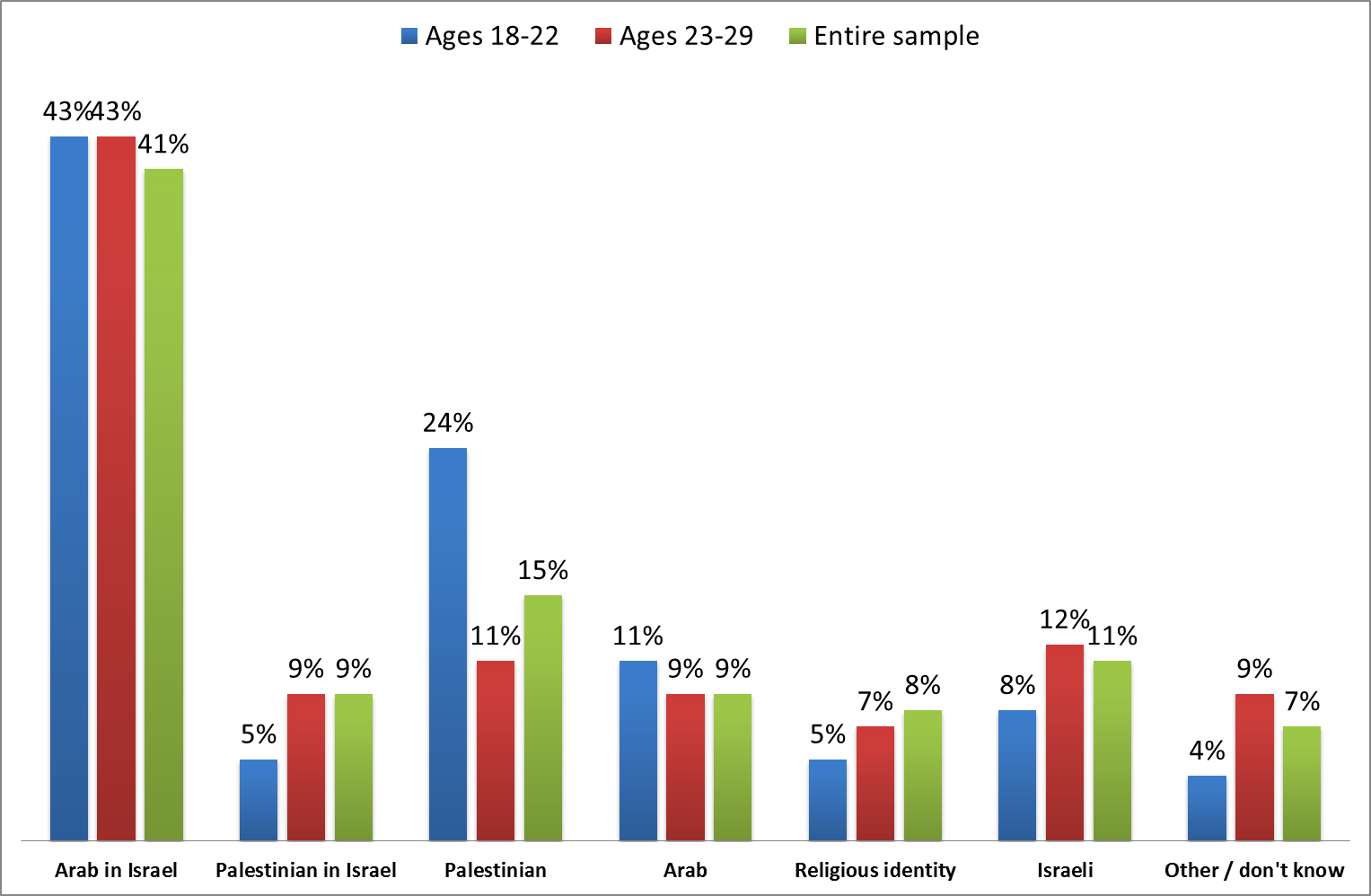

The percentage of young people in the entire sample (aged 18-29) who define their identity as "Arab in Israel" or "Arab citizen of Israel" exceeds 40%, and a smaller proportion of the different age groups (between 5% and 9%) include Palestinian identity as a component of their Israeli civic identity. However, it is noteworthy that about 35% of those aged 18 to 22 define their identity in purely national terms ("Arab" or "Palestinian") without a component of civic identity. This percentage is almost twice as high as it is in the 23 to 29 age group (20%). In fact, the percentage of respondents who self-identify by uniquely national terms is significantly higher amongst 18 to 22-year-olds than it is among any other age group in the survey population. In contrast, the percentage of those aged 23-29 who define their identity as "Israeli" (12%) is considerably higher than among those aged 18-22 (8%).

These findings show more than anything else the experience that falls upon the young generation with the completion of secondary school and with their first venture out of the home and into the spheres of employment and higher education. The first direct encounter with Jewish majority society and with an environment in which Hebrew language and culture dominates sometimes involves fears and experiences of frustration. Young Arabs emphasize national identity and suppress Israeli civic identity in response to manifestations of racism and alienation from Jewish society. Nevertheless, as the years pass, the younger generation adapts to the Jewish majority society and adopts a more balanced position: alongside the emphasis on national identity, the civic component of identity is strengthened.

Conclusion

The perception of young Arabs in Israel is influenced by the complex reality of their lives. In this reality, the challenges of daily life - the search for personal security, economic security, and a sense of stability and belonging - are entwined with the dilemma of personal and collective identity. The attitudes of the young Arabs in the survey reflect a shift between two poles: at one end is the reality of adult life in Israeli society in general, and at the other end is virtual reality and the world of social networks, which enables them to connect to their natural cultural and national space. On the one hand, it is possible to feel distrust of the state and its institutions and to criticize the state's path and institutions, and on the other hand, to have an appreciation for Israeli citizenship and the experience of living in the country, and to hold the aspiration to bring about political change.

The skeptical and critical positions of the Arab young generation should be put in a broader and more balanced context. These attitudes are a general expression of "youthful rebellion" from young people who oppose political and social conventions. The criticisms of the "Post-Oslo Generation" are directed not only at the state authorities, but also at the local Arab leadership and even the Palestinian leadership in the Palestinian territories. Nevertheless, ultimately the worldview of the younger generation crystallizes in the real environment in which they live, which is attested to through the changes that occur in young people’s attitudes of young people as age advances. There is no doubt that intelligent government policy will enable the young generation to integrate into the fabric of life in the country, thus benefiting both Arabs and Jews.

[1] This data was taken from the website of the Central Bureau of Statistics: www.cbs.gov.il. The data includes Arab residents of East Jerusalem. For further details see: Elie Rekhess and Arik Rudnitzky (eds.), Arab Youth in Israel: Between Prospects and Risk (Tel Aviv University: The Konrad Adenauer Program for Arab-Jewish Cooperation, 2008). [Hebrew]

[2] For an analysis of the full survey data, see Itamar Radai and Arik Rudnitzky, "Citizenship, Identity and Political Participation: Measuring the Attitudes of the Arab Citizens in Israel." Bayan: The Arabs in Israel, Issue 12 (December 2017).

[4] Internet Habits in the Arab Sector – Internet Society Survey, 2 August 2016. [In Hebrew].

[5] Zvi Eckstein and Momi Dahan, High Unemployment Among Arab Youth (Jersualem: The Israel Democracy Institute, The Caesarea Forum on Economy and Society, 2011); Sami Miaari and Nasreen Haddad Haji Yahiya. NEET Among Young Arabs in Israel (Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute, 2017). See: https://en.idi.org.il/media/9319/neet-among-young-arabs-in-israel.pdf

[6] Shabtai Bendt, “Between two worlds: the lives of Israel’s Arabs as students alongside Jews.” Walla! News Online: 4 August 2016. [Hebrew]

[7] Arik Rudnitzky, “Between al-Aqsa and Sakhnin: Arab Leadership and the Facebook Generation.” Bayan, Volume 6 (November 2015), pp. 7-11.

[8] Tawfiq Abd al-Fattah, “Activists: al-Hirak a-Shababi compels struggle.” Website arab48.com , 23 May 2018; Nidal al-Izza and Rolah Nasser-Mazawi, “Hirak Haifa: a look at the characteristics of change.” Website arab48.com , 23 May 2018. [Arabic]