Since 2016, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) has been overseeing the ambitious Vision 2030, which promises economic diversification and less dependence on oil rents, a more business-friendly and investor-friendly environment, bureaucratic reforms including privatization,[1] and transformation of the population’s “youth bulge” into an economic asset.[2] One of the centerpieces of the move away from oil is a proposed public offering of 5 percent of the state-owned oil company ARAMCO, and turning the remaining 95 percent into the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund.[3] To project a more welcoming image, through Vision 2030 the Saudis have also taken small steps to liberalize certain aspects of society, including ending the ban on women driving in June 2018,[4] opening the country’s first movie theater in more than thirty years,[5] and allowing women to attend public sporting events.[6]

These reforms have occurred in tandem with a more assertive Saudi foreign policy. Saudi Arabia, with Bahrain, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), decided to cut ties with fellow Gulf Cooperation Council member Qatar in June 2017 due to disagreements over a number of aspects of Qatar’s foreign policy.[7] In August 2018, relations between Saudi Arabia and Canada deteriorated quickly after the Canadian government publicly criticized the arrest of several female activists in the Kingdom. Saudi Arabia gave the Canadian ambassador in Riyadh 24 hours to leave the country,[8] put a new trade and investment agreement with Canada on hold,[9] suspended Saudi Airlines flights to and from Canada,[10] forced more than 12,000 Saudi students to transfer out of Canadian universities,[11] began selling all Canadian assets held by the Saudi Central Bank and pension fund “no matter the cost,”[12] and moved Saudi citizens receiving medical treatment in Canada out of the country.[13] Likewise, Saudi Arabia halted awarding government contracts to German companies in May 2018 owing to Germany’s continued economic engagement with the Kingdom’s main regional rival, Iran, and German criticism of Saudi Arabia’s interference in Lebanon’s internal affairs.[14] Since March 2015, a Saudi-led coalition with U.S. materiel and intelligence support has been directly involved in the Yemen Civil War trying to restore to UN-recognized government and defeat the Iran-backed Houthis. The coalition’s intervention has brought mostly negative attention to the Saudis and their allies: its airstrikes have been found to be “the leading cause of civilian casualties” in the conflict;[15] deals with al-Qaʿida in the Arabian Peninsula have strengthened the terrorist group;[16] the coalition’s air, land, and sea blockade has exacerbated Yemen’s cholera epidemic and food shortage;[17] and accounts of horrible human rights abuses in Emirati-run prisons in Yemen have been featured in the press.[18]

How have these controversial foreign policy choices affected Saudi efforts towards economic reforms and its economic performance? This issue of Iqtisadi will use a number of metrics to analyze Saudi economic performance over King Salman’s reign, concurrent to his son Mohammed bin Salman’s (MBS’s) heavy involvement in both areas. When King Salman became king in February 2015, he named MBS his successor as Minister of Defense and head of the newly-formed Council of Economic and Development Affairs,[19] the body that would produce the Vision 2030 plan. In particular, here we will compare some of the available data divided into two periods; namely, 2014-2016 will represent the time before Salman’s reign, and 2016-2018 will represent his reign so far. While Saudi proclamations may signal towards a more open and diversified economic system, its behavior towards fellow members of international economic, security, and political organizations are troubling developments that may dissuade investors from considering involvement in Vision 2030’s promised reforms.

Ease of Doing Business and Foreign Direct Investment

Vision 2030 offers a number of initiatives that will help attract foreign direct investment (FDI) to Saudi Arabia. Among them are “attracting and retaining the finest Saudi and foreign minds,”[20] improving government assistance to investors, making plots of government land available, helping prepare Saudi banks to assist investors, making customs processes more efficient for people and goods,[21] and entering agreements with other countries so that the flow of goods and people becomes more efficient both into and out of the country.[22] Through these adjustments, Saudi Arabia aims to increase FDI from 3.8 percent of GDP to 5.7 percent by 2030.[23]

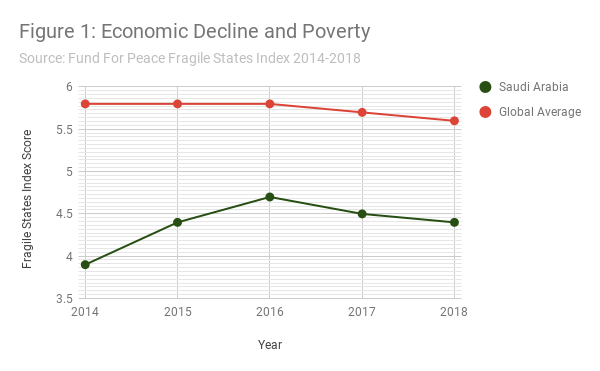

To assess the ease of doing business in Saudi Arabia, this essay will utilize scoring, repeated for a number of indicators from the Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index (FSI). FSI assesses the current state and future prospects for twelve indicators that are evenly distributed into four categories. For all indicators, a lower score demonstrates better performance.[24] Four of the twelve will be used in this assessment of the Saudi business environment:

- Economic Decline: This indicator focuses on both the formal and informal economy, scoring the country based on public debt, GDP, productivity, consumer confidence, business climate, and economic diversity.[25]

- Uneven Economic Development: This indicator assesses economic inequality and opportunities for skill development,[26] an important part of attracting and retaining companies’ presence.

- Human Flight and Brain Drain: This indicator assesses the country’s ability to retain demographics considered key to maintaining economic development,[27] among Vision 2030’s goals.

- Public Services: A number of the statistics included in the determination of this indicator, including those assessing education policy effectiveness and infrastructure,[28] are integral to assessing Saudi Arabia’s business environment and included in Vision 2030’s goals.

This assessment will account for year-to-year changes in Saudi scores between 2014 and 2018 as well as how Saudi scores compare to global averages in each of these categories for each year. In all four categories, Saudi Arabia’s scoring is below the global averages. In three – Economic Decline and Poverty, Uneven Economic Development, and Public Services (Figures 1-3) – FSI’s scoring shows improvement for the Saudis following King Salman’s ascent to the throne. For Economic Decline and Public Services, these changes came after worsening during the last two years of King Abdullah’s reign. The worsening economic outlook near the end of Abdullah’s reign is attributable to the sharp decline in oil prices through the last half of 2014.[29]

However, these improvements were accompanied by a decline during King Salman’s reign in Human Flight and Brain Drain (Figure 4). While Vision 2030 does call for attracting foreign workers to Saudi Arabia, this must be balanced with the development of the Saudi workforce. The 2011 Nitaqat Law codified Saudization, mandating companies to have a minimum percentage of their workers be Saudi citizens. Companies prioritized fulfilling these quotas instead of hiring the most talented candidates available, making Saudi Arabia a less attractive destination for potential employees.[30] Should the Saudis want to be an attractive destination for expatriate employees, they will need to make adjustments to the Nitaqat Law.

How have these developments affected inward foreign direct investment (FDI)?[31] Figure 5 shows slight growth from 2014 to 2015, followed by slight decline from 2015 to 2016, and then steep decline from 2016 to 2017. How can FDI have such a trajectory when the rule of King Salman has, according to FSI scores, created a more welcoming environment for capital infusion into Saudi Arabia? While the Saudis may be implementing rules to ease the flow of goods and people in and out of its borders, their handling of bilateral relationships is likely dissuading foreign investors from entering the Saudi market.

The Qatar crisis offers a telling example. As of 2016, the Saudi-Qatari bilateral trade relationship was relatively small: Among Saudi trading partners, Qatar was the 50th-largest import origin[32] and its 22nd-largest export destination.[33] But Saudi Arabia’s conduct towards Qatar signaled that pronouncements of rule of law and investment protection would be meaningless. Saudi Arabia completely shut down the flow of goods to and from Qatar, even to camels that frequently cross the demarcation.[34] With its only land border shut down, Qatar was also forced to use roundabout air and sea routes by the Saudi, Bahraini, and Emirati blockade.[35] Saudi plans to dredge the Salwa Canal – turning the Qatari peninsula into an island with a Saudi nuclear waste dump across the border from Qatar – remain in consideration.[36] These actions against alleged violations of Saudi sovereignty[37] may have been reasonable in the short-term, but the diplomatic spat continues today and may signal the end of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and its Common Market to ease the flow of goods across between its member countries.[38] Saudi actions towards Qatar hinge good relations on adherence to Saudi rules, similar to the recent crises Saudi Arabia has had with Germany and Canada. Investors may be wary of entering the Saudi market if criticism or imperfect adherence to Saudi policy demands could lead to the ruptures in economic ties.

The Saudi extrajudicial and extraterritorial assassination of Washington Post writer Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018 will likely represent a point of separation between Saudi Arabia and potential foreign investors. Khashoggi was banned from appearing in any Saudi media after he questioned the benefits of Donald Trump’s election victory to Saudi Arabia.[39] He wrote his first column for The Washington Post in September 2017,[40] and over the next year offered his critical perspective on Saudi Arabia’s economic reform efforts and foreign policy choices. In October 2018, Khashoggi entered the Saudi Consulate General in Istanbul, Turkey, to acquire a document necessary for his upcoming wedding, but never left.[41] Saudi Arabia initially denied any knowledge of his whereabouts, as MBS told Bloomberg reporters that Saudi Arabia was “very keen to know what happened to him.”[42] After a number of leaks from Turkish government and intelligence officials offered some idea of his grisly fate[43] and a short-lived joint Saudi-Turkish investigation,[44] the Saudis admitted that Khashoggi had died inside the diplomatic mission. The first admission unconvincingly referred to a chaotic fistfight,[45] before placing blame for the murder on a group led by General Ahmed al-Assiri, Deputy Director of the Saudi General Intelligence Directorate.[46]

The initial Saudi denial and evolving admission to its role in the death has created distance between Saudi Arabia and its traditional allies as well as key financial partners. In the United States, Saudi Arabia’s largest arms supplier, 22 Senators called for President Trump to initiate a Magnitsky Act investigation related to Khashoggi’s murder that could result in sanctions should MBS or other Saudi officials be found responsible.[47]

Key business figures have ended their relationships with MBS because of Khashoggi’s murder, including Virgin CEO Richard Branson, who ended his participation on two Vision 2030 tourism projects[48] and Y Combinator CEO Samuel Altman who terminated his participation in the Neom, the planned futuristic Saudi mega-city.[49] The Future Investment Initiative, held three weeks after Khashoggi’s death, was supposed to be an opportunity for the Saudis to show the world their deepening ties with key financial and tech figures from around the world, as Vision 2030 continued its major strides. Instead, the proceedings were overshadowed by those who chose not to attend, including the CEOs of SoftBank, JPMorgan, Credit Suisse, Uber, Blackstone, Mastercard, Siemens, and the London Stock Exchange, as well as IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde, World Bank President Jim Yong Kim, and U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin.[50] While other confirmed high-level attendees did not cancel their attendance, and SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son[51] and Mnuchin[52] still traveled to Riyadh and met with MBS and other Saudi officials, other business leaders and Western officials stayed away from Saudi Arabia and demonstrated that Saudi Arabia will not be able to target dissidents without economic consequence.

Oil Rents

By 2030, Saudi Arabia aims to increase non-oil goods share of its exports from 16 percent to 50 percent.[53] This would never be a simple task due to changes in the global market’s oil demand and the possibility that emerging technologies or the discovery of new reserves will have unforeseen effects on Saudi petroleum production and export. However, it is an integral step since the Saudi export basket has even less diversity than the economy overall (Figure 6).

Oil is a major issue in the Saudi rivalry with Iran, which is also characterized by proxy conflicts in Syria and Yemen and intense rhetoric from both sides. Both are members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which meets biannually to set common production goals that eventually influence the global price of oil.[54] In its earlier days, OPEC meetings were characterized by technocratic rather than political deliberations, with delegations prioritizing benefits for its oil industry over their governments’ respective political goals.[55]

With the end of sanctions on Iran following the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action to limit its nuclear program, many experts expected increased Iranian oil exports to spur its own economic growth and help bring down the price per barrel of crude.[56] However, during the December 2015 OPEC meeting in Vienna, Saudi Arabia brought its political goals into the meeting and refused to limit its production.[57] This would further decrease oil prices to their lowest point since October 2003, with prices falling below $30 per barrel twice in early 2016.[58] While this strategy may have helped to delay Iran’s renormalization within the international economic system, it served to further increase Saudi dependence on oil rents to provide services for its population. This impression may have also deterred potential investment in Saudi Arabia that is shown in Figure 5; by prioritizing increased oil production, Saudi Arabia has neglected its economic diversification efforts and focused its resources on countering Iran. The 2016[59] and 2017[60] OPEC deliberations regarding production cuts – both of which took place after Vision 2030’s rollout – led to production cuts acceptable for the OPEC and non-OPEC countries involved. However, should the Saudi-Iranian rivalry escalate again, the Saudis have shown through the 2015 production ramp-up that they would be willing to use oil as a weapon against its rivals – even if it harms them too.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia is intent on maintaining its leadership role in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East concurrently to much-needed economic reforms. However, by immersing itself in disputes with Iran and Qatar, it neglects its economic priorities, in fact hindering progress towards the goals outlined in Vision 2030. The economic blockade of Qatar demonstrates a serious ignorance of the rule of law, a low threshold for cutting off relationships, and a serious disinterest in making the flow of goods in and out of its borders more efficient. Relying on the crutch of oil may delay Iran’s recovery and reentry into the global economic system, but it also decreases the diversity of the Saudi economy and export basket and further entrenches Saudi economic dependence on oil rents.

These policies will certainly make investors think twice when considering investments in Saudi Arabia, and the Saudis seem aware of this sentiment: the Saudis reportedly postponed the ARAMCO IPO in August 2018.[61] In an October 2018 interview, MBS provided a detailed timetable for the IPO, including ARAMCO’s acquisition of the petrochemical company Sabic before the IPO takes place in “late 2020, early 2021.” However, during this interview MBS also offered a denial of a Saudi role in the extrajudicial, extraterritorial murder of Khashoggi,[62] after which many Western government and business officials moved to publicly distance themselves from the Saudis. Before taking such drastic foreign policy actions, Saudi leadership should consider the potential effects of such policies on its own economy and efforts to reform it.

[1] Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Council of Economic Affairs and Development, “Vision 2030,” April 26, 2016 , p. 13.

[2] Ibid., 37

[3] Paul Rivlin and Andrea Helfont, “Saudi Arabia's Plans for Change: Are they feasible?,” Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, May 31, 2016.

[4] BBC, “Saudi Arabia's ban on women driving officially ends,” June 24, 2018.

[5] Alexandra Zavis, “Saudi Arabia's first new cinema in decades holds its grand opening with a screening of 'Black Panther,'” The Los Angeles Times, April 19, 2018.

[6] Spencer Feingold, “Saudi women attend soccer match for first time,” CNN, January 12, 2018.

[7] Max Fisher, “How the Saudi-Qatar Rivalry, Now Combusting, Reshaped the Middle East,” The New York Times, June 13, 2017.

[8] Jon Gambrell, “Saudi Arabia Expels Canadian Ambassador Over Criticism,” U.S. News and World Report, August 6, 2018.

[9] Aziz Al Yaakoubi, “Canada defiant after Saudi Arabia freezes new trade over human rights call,” Reuters, August 5, 2018.

[10] Toronto Sun, “Saudi Airlines suspends Canadian operations starting Aug. 13,” August 7, 2018.

[11] Julia Knope, “What will happen to Saudi students enrolled in Canada?,” CBC, August 8, 2018.

[12] Simeon Kerr, “Saudi Arabia sells Canadian assets as dispute escalates,” The Financial Times, August 8, 2018.

[13] CNBC, “Riyadh to transfer all Saudi patients in Canada out of the country,” August 7, 2018.

[14] Benjamin Weinthal, “Saudi Arabia Stops New Business with Germany Over Its Pro-Iran Policy,” The Jerusalem Post, May 26, 2018.

[15] Human Rights Watch, “Yemen | World Report 2018,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[16] Maggie Michael, Trish Wilson, and Lee Keath, “AP Investigation: US allies, al-Qaida battle rebels in Yemen,” Associated Press, August 6, 2018.

[17] “Starvation, Cholera and War: Millions in Yemen Face 'Nightmare' After Saudi Arabia Shuts Borders,” Haaretz, November 8, 2017.

[18] The Guardian, “Sexual abuse rife at UAE-run jails in Yemen, prisoners claim,” June 20, 2018.

[19] Caryle Murphy, “In With the Old in the New Saudi Arabia,” Foreign Policy, February 25, 2015.

[20] “Vision 2030,” 37.

[21] Ibid., 50

[22] Ibid., 58

[23] Ibid., 53.

[24] The Fund for Peace, “Indicators | Fragile States Index,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[25] The Fund for Peace, “E1: Economic Decline and Poverty | Fragile States Index,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[26] The Fund for Peace, “E2: Uneven Economic Development | Fragile States Index,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[27] The Fund for Peace, “E3: Human Flight and Brain Drain | Fragile States Index,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[28] The Fund for Peace, “P2: Public Services | Fragile States Index,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[29] NASDAQ, “Crude Oil WTI (NYMEX) Price,” accessed October 31, 2018.

[30] Theodore Karasik, “There is good reason for the Saudi brain drain,” The National, February 15, 2015.

[31] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “World Investment Report 2018: Investment and New Industrial Policies,” June 6, 2018.

[32] The Observatory of Economic Complexity, “Import Origins of Saudi Arabia (2016),” accessed November 22, 2018.

[33] The Observatory of Economic Complexity, “Export Destinations of Saudi Arabia (2016),” The Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed November 22, 2018.

[34] Ibrahim Saber and Tom Finn, “Camels caught up in Qatar feud reunited with their owners,” Reuters, June 20, 2017.

[35] Hassan Hassan, “Qatar Won the Saudi Blockade,” Foreign Policy, June 4, 2018.

[36] Hassan Sajwani, “Salwa Canal Arab quartet’s silent message to Qatar,” Gulf News, July 8, 2018.

[37] The National, “Saudi Arabia statement on severing Qatari ties,” June 5, 2017.

[38] Gulf Cooperation Council, “GCC Economic Nationality,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[39] Middle East Eye, “Saudi journalist banned from media after criticising Trump,” December 5, 2016.

[40] Jamal Khashoggi, “Saudi Arabia wasn’t always this repressive. Now it’s unbearable.,” The Washington Post, September 18, 2017.

[41] Carlotta Gall, “What Happened to Jamal Khashoggi? Conflicting Reports Deepen a Mystery,” The New York Times, October 3, 2018.

[42] Stephanie Flanders, Vivian Nereim, Donna Abu-Nasr, Nayla Razzouk, Alaa Shahine and Riad Hamade, “Saudi Crown Prince Discusses Trump, Aramco, Arrests: Transcript,” Bloomberg, October 5, 2018.

[43] David D. Kirkpatrick and Carlotta Gall, “Turkish Officials Say Khashoggi Was Killed on Order of Saudi Leadership,” The New York Times, October 9, 2018.

[44] Reuters, “Saudi team arrives in Turkey for Khashoggi investigation: sources,” October 12, 2018.

[45] Simon Tisdall, “No one is convinced by the Saudi story of a ‘fistfight’ that went wrong,” The Guardian, October 20, 2018.

[46] Martin Chulov, “Saudi prince pins blame for Khashoggi death on favoured general,” The Guardian, October 19, 2018.

[47] Bob Corker (R-Sen., TN), “Corker Statement on Saudi Arabia Claims Regarding Death of Jamal Khashoggi,” October 20, 2018.

[48] The Telegraph, “Sir Richard Branson freezes Saudi business ties over disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi,” October 11, 2018.

[49] Sam Biddle, “Some Silicon Valley Superstars Ditch Saudi Advisory Board After Khashoggi Disappearance, Some Stay Silent,” The Intercept, October 11, 2018.

[50] Zahraa Alkhalisi and Jethro Mullen, “Who's at Saudi Arabia's 'Davos in the desert' and who's staying away,” CNN, October 23, 2018.

[51] The Japan Times, “SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son met Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh: sources,” October 25, 2018,.

[52] Alan Rappeport, “Mnuchin Defends Trip to Saudi Arabia Amid Uproar Over Khashoggi Killing,” The New York Times, October 21, 2018.

[53] “Vision 2030,” 61.

[54] Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, “OPEC 174th Meeting concludes,” June 22, 2018.

[55] Hamid Elyassi, “Survival of OPEC and Saudi–Iran Relations—A Historical Overview,” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 5, No. 2 (June 2018): 141.

[56] Ian Bremmer, “5 Ways the Nuclear Deal Will Revive Iran's Economy,” Time, July 16, 2015.

[57] Rania El Gamal, Alex Lawler, and Reem Shamseddine, “OPEC fails to agree production ceiling after Iran pledges output boost,” Reuters, December 4, 2015.

[58] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Cushing, OK WTI Spot Price FOB,” accessed November 22, 2018.

[59] Elyassi, “Survival of OPEC and Saudi–Iran Relations,” 137.

[60] Alex Lawler, Rania El Gamal, and Shadia Nasralla, “OPEC, Russia agree oil cut extension to end of 2018,” Reuters, November 30, 2017.

[61] Michael J. de la Merced and Clifford Krauss, “Saudi Aramco Is Said to Postpone Its Potentially Record-Breaking I.P.O.,” The New York Times, August 22, 2018.

[62] Flanders, et al, “Saudi Crown Prince Discusses Trump, Aramco, Arrests” (see note 42).