Introduction

Although International Relations is conventionally conceived as the study of states in the international system, growing attention has focused in recent years on the role of non-state actors. Specifically, it has centered on the number of state-like entities and their place in interacting with established, recognized states. A number of different terms have been given to these state-like entities: quasi states, de facto states, unrecognized states and in the context of federalism, sub-state units.[1]

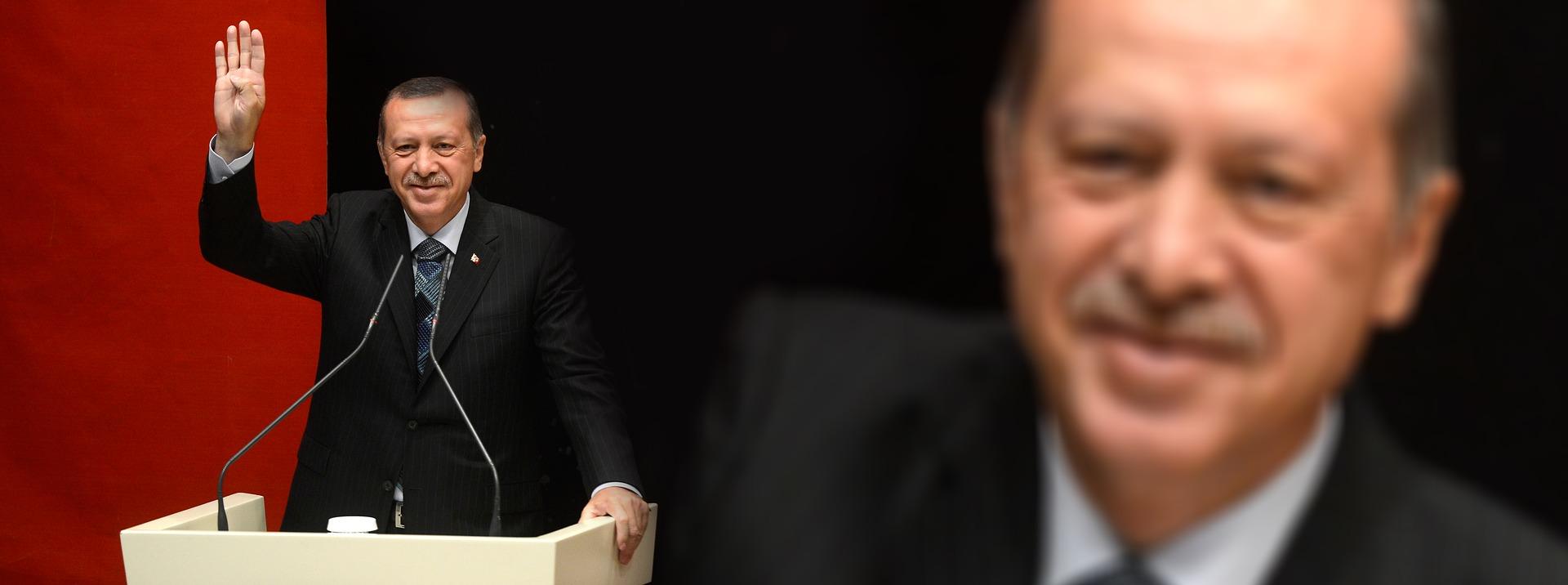

This article considers Turkish relations under Erdoğan with two such political entities in the Middle East that are an important part of Turkish foreign policy: the Kurdistan Regional Government and the Palestinian National Authority. It focuses broadly on the Turkish policy towards their aspirations to independent statehood and achieving international recognition. Specifically, the Turkish approach towards two recent issues is highlighted. Firstly, the September independence referendum conducted in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and secondly, the international response to the December statement by President Trump on Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Turkey and the formation of Kurdish and Palestinian Quasi-states

Of course, the Republic of Turkey and its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire, have long historical connections with the Kurds and with the Palestinians. Indeed, these two ‘stateless peoples’ exhibit a commonality, which was identified by the late Professor Fred Halliday; both have experienced the syndrome of post-colonial sequestration: “where countries or peoples have – at a decisive moment of international change, amid the retreat of imperial or hegemonic powers – failed (through bad timing and/or bad leadership) to establish their independence.”[2] The decisive moments can be identified as around the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the end of the Second World War.

In the intervening decades through their struggle against incorporation and occupation they eventually fashioned political entities that resemble states. The 1933 Montevideo Declaration on Rights and Duties of States is one way of defining a state: this Declaration holds that to qualify as a state the entity must have (1) a permanent population; (2) a defined territory; (3) a government; and (4) the capacity to enter into relations with other states. The Kurdistan Regional Government and the Palestinian National Authority appear to fulfil these criteria to a greater or lesser extent. In the term ‘quasi-state’ the prefix quasi is used to show that something is almost, but not completely, the thing described. The following section sets Turkish relations with these quasi-states in brief historical context, then focuses on the two recent contemporary issues being examined.

Turkey, the Kurds and the referendum on independence

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire the Kurds seemed poised to obtain a homeland as stated in the Treaty of Sèvres (1920). However, with Turkey resurgent under the leadership of Kemal Atatürk, the subsequent Treaty of Lausanne (1923) omitted any reference to a Kurdish homeland. Instead the Kurds became constituted as a concentrated geographic minority in the three Ottoman successor states of Turkey, Iraq and Syria, as well as incorporated into the new dynasty of Pahlavi Iran. Under Atatürk, a policy of Turkification was attempted with corresponding denial of Kurdish identity and accompanying use of force, leading eventually to the rise of the armed resistance of the PKK in the 1980s. Any assertion of Kurdish identity in Iraq or elsewhere was feared as it could provide a precedent or example to the Kurds in Turkey. Accordingly, Turkey maintained a hostile stance to the Kurdistan Regional Government as it developed in the no-fly zone following the 1991 Gulf War.[3] However, following the 2003 Iraq War and the development of federal Iraq, Turkey gradually shifted from unrelenting hostility to ever closer relations with the KRG, and particularly with the Barzani-dominated KDP. Turkey sought through its dominance of trade and goods in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to be able to manage Kurdish aspirations and limit the PKK’s ability to operate. Similarly, Turkey provided an essential conduit for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to export its oil and gas, even on extremely favorable terms for Turkey.

It might be thought that this would lead Turkey to look favorably on the Kurdish aspirations to hold the referendum on independence in September 2017. However, crucially, the internationally recognized sovereign authority (the central government in Baghdad) had opposed the referendum from the start: Iraqi Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi, declared it unconstitutional and the Iraqi Supreme Court ordered the suspension of the referendum. In the absence of support for the referendum from the sovereign state, major international and regional powers (except Israel), as well as intergovernmental organizations were unanimous in opposing the unilateral decision to hold the referendum, and actively sought to dissuade the KRG from proceeding with it.[4] Erdoğan convened a meeting of the Turkish National Security Council and warned that there would be “serious consequences” if the referendum went ahead. Turkish, Iranian, and Iraqi foreign ministers met at the United Nations in order to coordinate their response to Erbil’s referendum.[5]

The reaction to the referendum came a few days after it was held, when Baghdad announced that it would ban international flights to the Kurdistan Region’s airports, beginning on September 29. Further measures followed from Baghdad, which included coordinated Iraqi/Turkish military exercises, a parliamentary authorization of the use of force, and ultimatums to hand over control of border posts and Kirkuk. On October 16, the Iraqi Armed Forces, federal police and the Hashd al Shaʿbi [Popular Mobilization Forces] Shiʿi militias took control of Kirkuk. The Kurdish dreams and aspirations for an independent state were crushed only a few weeks after their referendum, which had been conducted in a spirit of celebration. Turkey played an important part in supporting Baghdad’s efforts to suppress the KRG’s referendum on independence. However, not surprisingly, Turkish policy is completely different in connection with the Palestinian quasi-state’s aspirations for independent statehood and international recognition.

Turkey, the Palestinians and President Trump’s statement on Jerusalem

Turkey was the first majority Muslim state to recognize Israel and now maintains support for a two-state solution based on pre-1967 borders, with East Jerusalem as capital of a Palestinian state. This issue represents an expression of broad popular opinion in Turkey, not just a matter of policy at elite level. Following the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, Turkey actively supported the efforts of the State of Palestine (declared by the PLO in 1988) to gain recognition in international fora. This has included supporting its bid for membership in UNESCO in 2011 and its upgrade to non-member observer state in the United Nations in 2012. Turkey broke off diplomatic relations with Israel in 2010 following the killing of ten Turkish activists by Israeli commandos as they boarded a flotilla in international waters, which was attempting to break the Israeli blockade of Gaza. Diplomatic relations were only restored in 2016 and they now seem set to enter a further period of great strain following President’s Trump recent statement recognizing Jerusalem as capital of Israel and instructing the U.S. State Department to prepare the U.S, embassy to move from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Erdoğan warned President Trump against recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and further advised that it could lead to Turkey severing relations with Israel again. Further, Erdoğan convened an emergency summit of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). In advance of this summit, President Erdoğan met with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to discuss and coordinate positions. The United States now stands on its own in its position on Jerusalem; Russia specifically recognized West Jerusalem as the Israeli capital, and Prime Minister Netanyahu has been rebuffed by the European Union as he sought to garner support for wider recognition before any final status peace negotiations.[6] Ironically, in the same way that the President Barzani found little international state support for his independence referendum, now President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu find themselves isolated internationally in their position on a united Jerusalem as capital for Israel. Turkey has played a key role in promoting such stances internationally, in both cases.

Balancing states and quasi-states in Turkish foreign policy

In its relations with the Kurdish and Palestinian quasi-states, Turkey under Erdoğan must weigh its economic, political and cultural interests, in connection with its relations with the central Iraqi government in Baghdad and with Israel. For example, it may not want to embolden or support Baghdad to such an extent that the KRG ceases to act as a buffer to Iranian influence in Iraq. Similarly, Turkey has important economic relations with Israel. In reaction to Erdoğan’s warning to Trump, Israeli Education Minister Naftali Bennett countered that Erdoğan never missed an opportunity to attack Israel and that it was better to have a “united Jerusalem” than Erdoğan's sympathy or approval. Furthermore, Netanyahu said that he would not endure lectures from Erdoğan while he was engaged in war against Turkey’s Kurdish population and denying them their human rights. Thus, a political triangle exists in which Israel supports the Kurds in Iraq as part of their periphery security policy, whilst Turkey supports the Palestinians as part of its political and cultural presence in the region. Maintaining this balancing act will undoubtedly be a challenge for Turkish policy in the coming years.

Conclusion

Both the Kurds and the Palestinians lost out terribly in the state formation processes initiated by British imperialism following the demise of the Ottoman Empire. As a solution to the problems of ‘post-colonial sequestration,’ Halliday enjoined the peoples affected to campaign for human and democratic rights including federalism, whereby if achieved, in time all issues, including independence, could be constructively discussed. We can conclude that quasi-states loom just as large as fully recognized states in Turkey’s regional outlook. Developments in these quasi-states will form an important focus of Turkish policy in the Middle East. Turkey’s position may yet have a significant impact in both of the cases examined here, including its efforts to promote economic development as conflict resolution. However, bearing in mind recent events and their impact on prospects for a peaceful resolution to these conflicts, from this author’s perspective, one can perhaps unfortunately concur with Halliday, that “the time for a realistic optimism, for [Kurdistan] and Palestine, is not yet at hand.”

Dr. Francis Owtram is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom.

[1] Nina Caspersen and Gareth Stansfield (eds.), Unrecognized States in the International System (Oxon: Routledge, 2011).

[2] Fred Halliday, “Tibet, Palestine and the Politics of Failure,” OpenDemocracy, 13 May 2008. Last accessed 14 December 2017.

[3] Francis Otram, “Kurds in Iraq: From Sykes-Picot to No-Fly Zones and Beyond,” OpenDemocracy, 18 September 2017. Last accessed 14 December 2017.

[4] Bill Park, et al., “Field Notes: On the independence referendum in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and disputed territories in 2017,” Kurdish Studies 5, no. 2 (October 2017): 199-214.

[5] Cengiz Çandar, “Turkey's threats against Kurdish referendum vague but deliberate,” Al-Monitor , 22 September 2017. Last accessed 14 December 2017.

[6] “EU's Federica Mogherini rebuffs Netanyahu on Jerusalem,” BBC Middle East,11 December 2017.